The abuse of power

In 1971, Stanford Psychology Professor Philip Zimbardo conducted a simulation study on the psychology of imprisonment. The results were compelling

Words: Olivia Borg

Last year, The Stanford Prison Experiment film was released. The movie is an account of the Stanford prison experiment in which students played the role of a prisoner or a prison guard conducted at Stanford University under the supervision of psychology professor Philip Zimbardo in 1971.

Professor Zimbardo conducted the experiment to test the hypothesis that the personality traits of prisoners and guards are the chief cause of abusive behaviour between them. In the experiment, Zimbardo selected 15 male students to participate in a 14-day prison simulation to take roles as prisoners or guards. They received $15 per day, and the experiment was conducted in a mock prison located in the basement of Jordan Hall, the university’s psychology department building.

The outcome was that the students who were role-playing guards became abusive, as well as the professor himself. It became so intense so quickly that two students who played the role of prisoners quit the experiment early, and Zimbardo abruptly stopped the entire experiment after

only six days.

Professor Zimbardo: “How we went about testing these questions and what we found may astound you. Our planned two-week investigation into the psychology of prison life had to be ended after only six days because of what the situation was doing to the college students who participated. In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.”

Here’s what happened… The end result of the experiment:

“On the fifth night, some visiting parents asked me to contact a lawyer in order to get their son out of prison. They said a Catholic priest had called to tell them they should get a lawyer or public defender if they wanted to bail their son out! I called the lawyer as requested, and he came the next day to interview the prisoners with a standard set of legal questions, even though he, too, knew it was just an experiment.

At this point it became clear that we had to end the study. We had created an overwhelmingly powerful situation – a situation in which prisoners were withdrawing and behaving in pathological ways, and in which some of the guards were behaving sadistically. Even the “good” guards felt helpless to intervene, and none of the guards quit while the study was in progress. Indeed, it should be noted that no guard ever came late for his shift, called in sick, left early, or demanded extra pay for overtime work.

I ended the study prematurely for two reasons. First, we had learned through videotapes that the guards were escalating their abuse of prisoners in the middle of the night when they thought no researchers were watching and the experiment was “off”. Their boredom had driven them to ever more pornographic and degrading abuse of the prisoners.

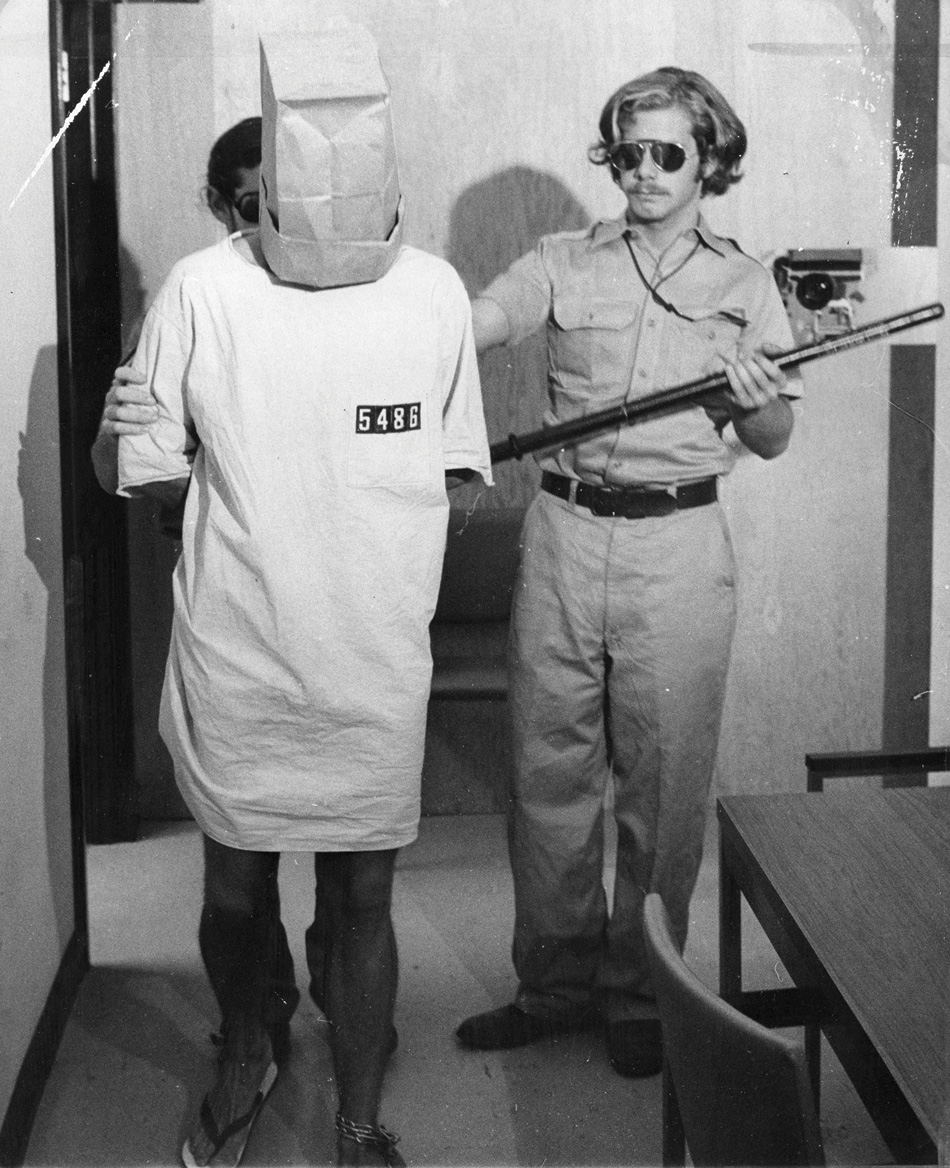

Second, Christina Maslach, a recent Stanford Ph.D. brought in to conduct interviews with the guards and prisoners, strongly objected when she saw our prisoners being marched on a toilet run, bags over their heads, legs chained together, hands on each other’s shoulders. Filled with outrage, she said, “It’s terrible what you are doing to these boys!” Out of 50 or more outsiders who had seen our prison, she was the only one who ever questioned its morality. Once she countered the power of the situation, however, it became clear that the study should be ended.

And so, after only six days, our planned two-week prison simulation was called off.

On the last day, we held a series of encounter sessions, first with all the guards, then with all the prisoners (including those who had been released earlier), and finally with the guards, prisoners, and staff together. We did this in order to get everyone’s feelings out in the open, to recount what we had observed in each other and ourselves, and to share our experiences, which to each of us had been quite profound.

We also tried to make this a time for moral reeducation by discussing the conflicts posed by this simulation and our behaviour. For example, we reviewed the moral alternatives that had been available to us, so that we would be better equipped to behave morally in future real-life situations, avoiding or opposing situations that might transform ordinary individuals into willing perpetrators or victims of evil.

Two months after the study, here is the reaction of prisoner #416, our would-be hero who was placed in solitary confinement for several hours:

“I began to feel that I was losing my identity, that the person that I called Clay, the person who put me in this place, the person who volunteered to go into this prison – because it was a prison to me; it still is a prison to me. I don’t regard it as an experiment or a simulation because it was a prison run by psychologists instead of run by the state. I began to feel that my identity, the person that I was that had decided to go to prison was distant from me – was remote until finally I wasn’t that, I was 416. I was really my number.”

Compare his reaction to that of the following prisoner who wrote to me from an Ohio penitentiary after being in solitary confinement for an inhumane length of time:

“I was recently released from solitary confinement after being held therein for thirty-seven months. The silence system was imposed upon me and if I even whispered to the man in the next cell resulted in being beaten by guards, sprayed with chemical mace, black jacked, stomped, and thrown into a strip cell naked to sleep on a concrete floor without bedding, covering, wash basin, or even a toilet… I know that thieves must be punished, and I don’t justify stealing even though I am a thief myself. But now I don’t think I will be a thief when I am released. No, I am not rehabilitated either. It is just that I no longer think of becoming wealthy or stealing. I now only think of killing – killing those who have beaten me and treated me as if I were a dog. I hope and pray for the sake of my own soul and future life of freedom that I am able to overcome the bitterness and hatred which eats daily at my soul. But I know to overcome it will not be easy.”