Controversial Beauty

Anna Marie Galea explores why a photograph that defined beauty in the 19th century challenges our expectations of beauty standards today.

Words: Anna Marie Galea

It’s the modern meme that has launched a thousand reactions. Yet in the superficial sphere, which is the Internet, few have challenged the story behind the Princess Qajar photograph doing the World Wide Web rounds or looked beyond the trappings of what many people in the modern Western world define as beautiful.

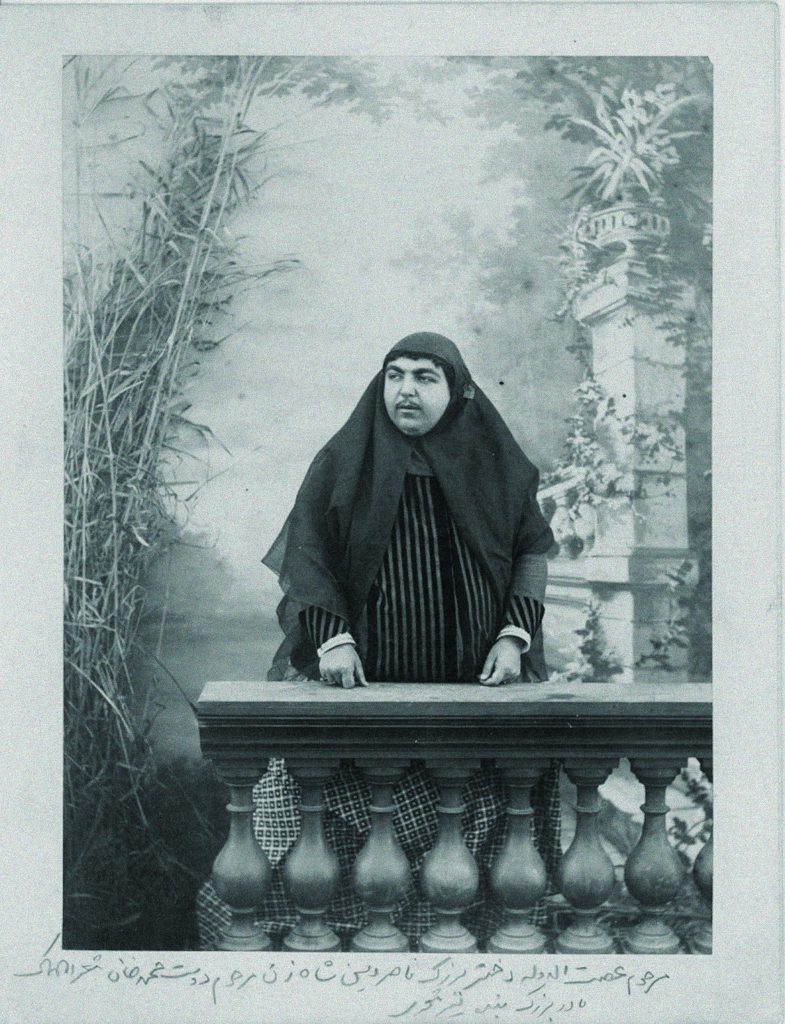

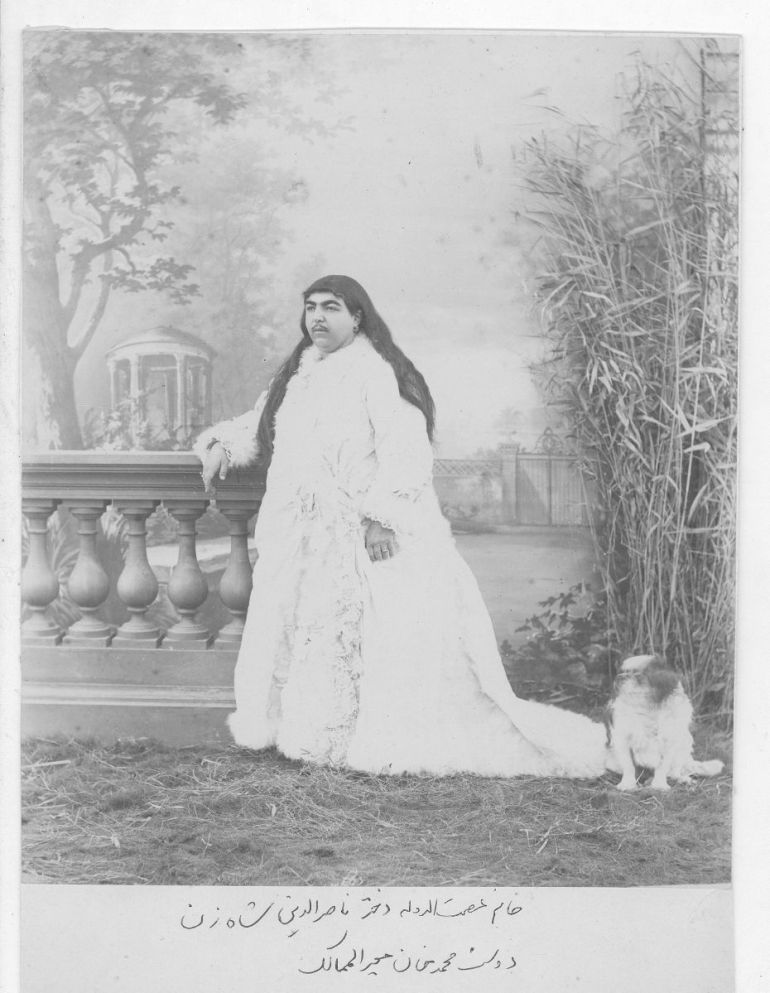

A quick glance at the black and white photo, which has graced so many Facebook walls in the past months, shows the Princess Qajar looking like a squat man who has found his way into a woman’s wardrobe and worn the whitest, most conspicuously opulent dress he could find. This is in itself guaranteed to raise an eyebrow or three.

However, the creator of this colourful black and white meme was not happy with just leaving it at that and the meme continues to state that 13 men committed suicide because the princess refused to marry them. The internet lapped it up like thirsty camels in the desert and lambasted the poor protagonist’s appearance left, right and centre.

With the boom of apps like Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat, it is not only become vastly apparent that people no longer value the importance of the source of the information they are consuming (or its quality or longevity for that matter); these apps have also succeeded in bringing out the worse in people’s characters and insecurities. Appearance has become all, and woe betide he who does not get with the glossy programme.

Upon digging a little bit deeper into Princess Qajar’s backstory, I quickly realized that this much-mocked woman probably did not even exist; in fact, there was no Princess Qajar at all. The woman in the photo is Princess Fatemah Khanum “Esmat al-Dowleh”, who was part of the Qajar dynasty.

She was born in a time when women in Persia would be married off at a very young age by their fathers and would not have the opportunity to mix with members of the other sex, let alone have them commit suicide over their supposed refusal. However, as far as I’m concerned historical facts aside, I find the public’s reaction to it perhaps even more worrying than the glaring historical inaccuracies.

International standards of beauty have always been different and varied until globalisation, and particularly, the internet began to subconsciously tell us otherwise. In Arab cultures, for example, a bigger woman was always seen to be more desirable simply because bigger woman denoted fertility which is still a primary issue for many cultures.

In Mauritania, there are actual fat farms where young girls are taken and force-fed in order to be able to make them more desirable to suitors. And having an abundance of facial and body hair is no different. It is not uncommon for women from southern countries to have thicker and darker hair than their northern counterparts and there was a period in Persian history in the 19th century where having thick upper lip hair was seen as a sign of beauty.

Ironically, despite our supposed strives in gender equality and fluidity, there seems to have been less fuss about this issue in nineteenth-century Iran and in fact, in a paper entitled ‘Let’s Talk About Sex and Gender: The Case of Iran A Book Review’ by Hafsa Kanjwal, the author states: ”It is through the Persian paintings of the Qajar time period that Najmabadi is able to argue that ideas of beauty during this era were not gendered. Rather, certain traits such as a lean waist, thick eyebrows, and a thin moustache were considered beautiful, irrespective of the holder’s gender.

In one such painting, entitled Embracing Lovers by Muhammad Sadiq, the attribution of male or female to the two figures becomes difficult, as they both exhibit these uniform traits of beauty. Najmabadi argues that there were no notions of “female beauty” or “male handsomeness”—both were identical.”

Looking at that paragraph alone, it then seems sadly ironic that the democratisation of the Internet has led to a supposed democratisation of how one must look in order to be seen as desirable. The Internet’s need to market women’s looks in particular as a commodity where one size fits all is worrying, if not highly unacceptable.

There was a time when diversity was celebrated and, if not always understood, was at least accepted. However, thanks to a lack of role models who vaguely look like them, many women who are not born tall, thin, blonde and blue-eyed have rejected their natural bodies and look at themselves with loathing. In a world where women who look like Chiara Ferragni are venerated, it is little wonder that everyone who is not born blonde wants to be a Kardashian.

There needs to be more awareness not only about the things we choose to share on our personal social channels but also on what makes each and every human unique.

It should not come as a shock to us that a woman with a moustache was valuable and beautiful enough to die for (even though there are no facts to support this unlikely tale). Maybe we should stop bandying around terms like feminism if we are unable to grasp the tolerance and respect for differences that should lie at the root of this term. Our strengths lie in our differences, not in our similarities.