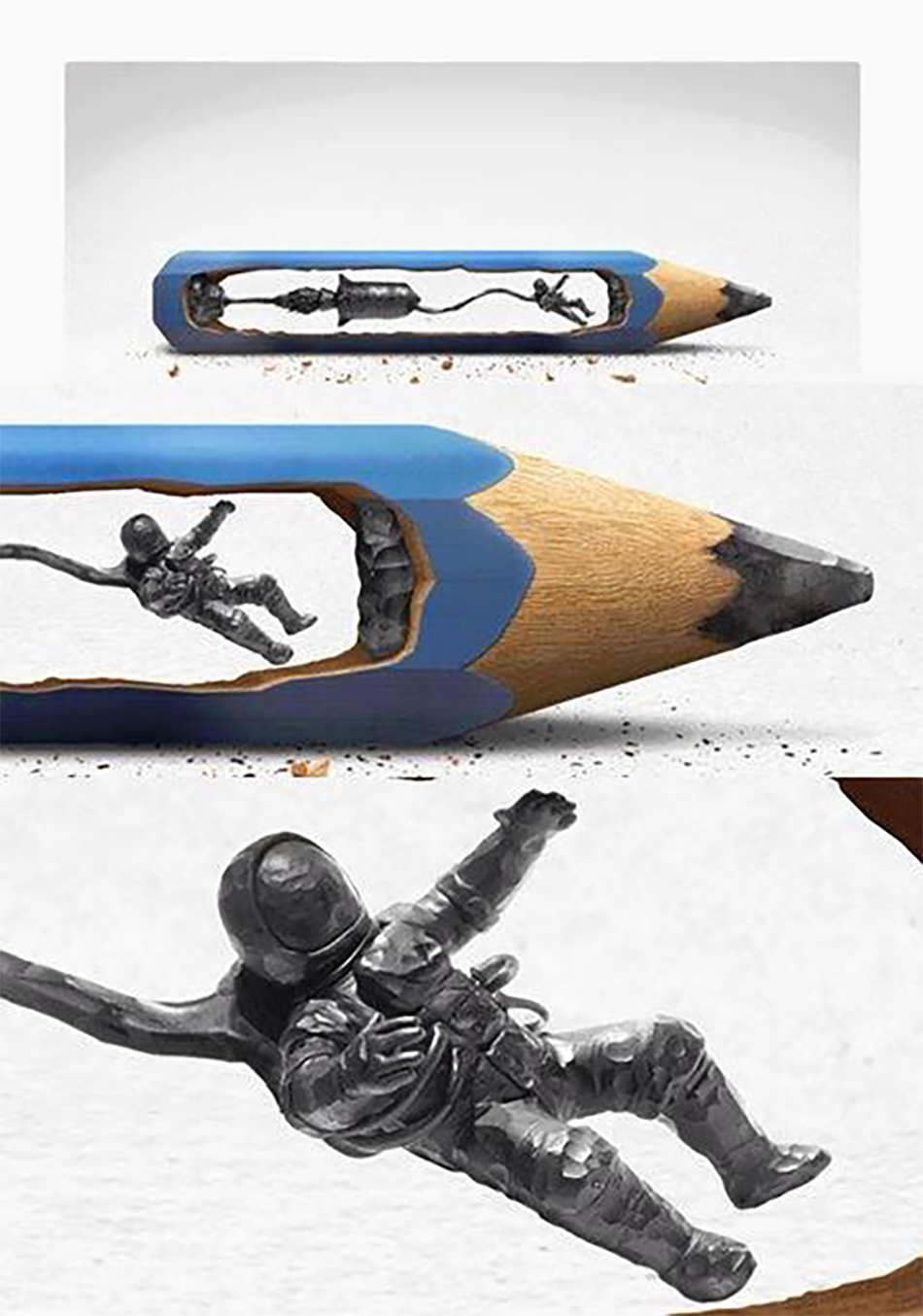

A pencil & a dream

VAMP speaks to the amazing pencil sculptor Dalton Ghetti...MIND BLOWING!!

Conversation with Dalton Ghetti By Julian Cardona Photos: Sloan Howard

Ladies and gentleman I present you the great pencil artist, Mr Dalton Ghetti.

Of all privileged people who deserved this rare accolade, he would sit most comfortably amongst them. Special would be another adjective, one that I use in the nicest, most admiring ways. Consider this. When I look at an old, beaten pencil I see another potential add-on to my vast collection of clutter and my instinct would probably induce me to throw it away. But not him. He would probably grab my hand and stop me from murder; take away the retired but still dignified pencil, and in it he would see a church, a chain, a handsaw with graphite teeth, a hammer with a graphite head, a sewing needle, letters of the alphabet, a heart, a tower, a pumpkin or even, well, a giraffe.

Born and raised in Brazil, he moved to Bridgeport Connecticut USA in 1985 at the inspirational age of 24. He got a degree in Architecture and started working as a Carpenter and house remodeler. When he is not working on houses, he puts on his artistic hat and with a pencil and assorted tools his magic starts to unravel.

As he picked up the phone from his house in Bridgeport he greeted me with a soothing voice which conveyed a humbleness that does not seem to belong to talent. After a quick introduction (and a pinning down of Malta on the world map) I was eager to start with a nostalgia question. I figured, one does not simply wake up one morning and decides to sculpt pencils-such inspiration would probably start very early. “As far as I can remember,” he started nostalgically, “I’ve always had my own tools, even at school. I’ve always been a hands-on kind of guy. I created my own tools, my own toys and my own go-carts. I also tried a lot of different materials like stone, wood, wax and soap. This was probably somewhere around the age of 9.” How many children can boast of creating their own toys in this day and age? Of course when your toys are Smartphones and Ipads, it becomes a little bit hard to create them with a chisel and a hammer. The anti-capitalist in me would probably argue that modern technology is depriving the world of talents like Dalton. But Mr Ghetti did not share my negativity. “I do see what’s happening around me. But today it is so easy to exchange info and connect to each other that this definitely helps to shape ideas and it inspires people to create.”

…”I was always interested in chains, i find them fascinating. It looks deceptively simple, but as it turned out, it proved one of the most challenging projects of my life”…

For such a hands-on artist like Dalton I did not expect such admiration for technology. “I‘ve always appreciated the small things in life like insects, plants, moss, but it was actually the event of nanotechnology that intrigued me enough to start working on the very small. It was somewhere in the late 70’s and one must remember that we had no technology back then.

So I decided to challenge myself: How small a thing can I create with just my bare hands and naked eyes? ” It was a tall order indeed. I was particularly intrigued by the approach. How does one go from looking at an old pencil to creating a miniature sculpture? “It starts with an idea in my head and then a drawing. I get ideas from all around me, from all of life.”

For example, one of the most interesting sculptures is the one with two enchained pencils, called simply “Chain”. The story behind it is perhaps even more interesting than the result itself. “I went to a lot of shipyards and saw a lot of chains and this inspired the chain project. I was always interested in chains, I find them fascinating. It looks deceptively simple, but as it turned out, it proved one of the most challenging projects of my life. I started with a pencil and carved out the wood until I hit the graphite. Then I had a straight rod of graphite in the middle. The idea was to carve each link of the chain individually and the first one was an absolute nightmare.” As it turned it out it was not only an artistic feat, but even a greater logistical problem. “See, I needed one hand to hold the pencil, the other to hold the loose part and another hand to carve it. Problem is, I have only got two hands! I had to stop and was unable to continue. ” The solution proved to be a very intricate one. “I had to hold the pencil on the palm of my hand and carve with the other free hand. I had to control my breathing and the rhythm of my heartbeat as every little movement was destabilizing. This agonizing process, from the idea to completion, took me two years. It was the hardest project ever.”

The chain project may have been Dalton’s most labour intensive creation, but on an emotional level, there was an even bigger project on its way and this would last 10 years. On September 11, 2001 Dalton was in a park not too far from the towers.

“My art comes from my heart. I don’t want money to dictate what i do. The lack of money removes the time pressure. I’ve seen the way that money changes people”

“I could see smoke coming out of the buildings. I cried so much, I had tears flowing down my cheeks. This gave me an idea. I went home, took out my journal and drew a tear drop and inside this tear drop I drew many other tiny tear drops. I decided that every day, I would make a tiny tear drop made out of graphite from recycled pencils. It was my way of honouring them.” Ghetti carved a graphite tear drop, each the size of a grain of rice, every day for 10 years and the result was 3000 graphite tear drops for every victim of the September 11 tragedy. One of Dalton’s proudest moments came on the September 11, 2011 at the unveiling of his art at the New Britain Museum of American Art. “It was an emotional day. I had people hugging me in tears and thanking me. It was an emotional day.”

In spite of the obvious talent and enormous passion that drives him, Dalton still chooses not to create art for a living. “My art comes from my heart. I don’t want money to dictate what I do. Very early on I decided that I will do only the things that I like for myself. There are some who get mad at me because they want to buy my stuff, but I tell them it’s not for sale. The lack of money removes the time pressure. I’ve seen the way that money changes people; changes the way they do things. ” He then went on to make a harsh confession. “You see, there are days that I cannot even look at a pencil!” One cannot be surprised at this, given the enormous intensity that goes into each piece of work. The hours of logistical considerations, and the meditative state he descends into would be incompatible with a 9 to 5 timetable that money often drags us into. There is also the issue of timelessness. “What if someone buys my art and breaks it? My pieces are all very fragile and by keeping them I make sure that they are preserved. I like to donate my art to museums but I will not exchange them for money. My art will be a perpetual gift to humanity.”

So what about those who want to make art for a living? He answers simply: “They should create what’s in their hearts. They should create as much as they can! It’s so easy to share information these days; the whole world can see what you’re doing. Long time ago one could only see art in a gallery, but that has changed.” We concluded with a few thoughts on Maltese artists who create art in a country which can never offer monetary rewards. I asked him if he had any advice for these often frustrated souls. “Size doesn’t matter anymore. You just put your art out there and if it’s done from the heart there are going to be people out there who relate to it.”

There is no doubt that Mr Ghetti is an authority when speaking about “creating from the heart”; his whole portfolio is a testament to this. As we said our goodbyes I found myself thinking how glad I was that in this mad world, it was still possible to find genuine artists like Mr Ghetti that radiate inspiration. Maybe he’ll come to Malta one day: he assures me that he’d be more than happy if the right arrangements can be made. And I sure hope they can: I would be the first in line, I assure you, listening to that tone whose humbleness does not seem to belong to talent, or, on the contrary, a humbleness that really should always belong to talent.