Forms of madness

vamp meets with flore gardner, a french-scottish visual artist, living and working in edinburgh.

Your journey from studying medicine

to pursuing a Ph.D. in Fine Art is quite unique. How do you feel your background in medicine influences your drawing practice?

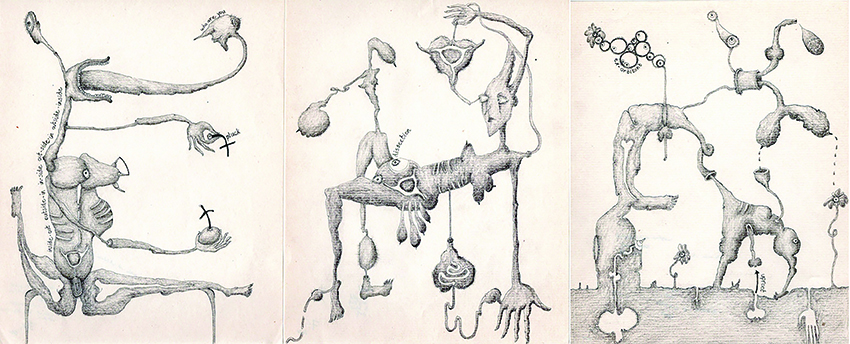

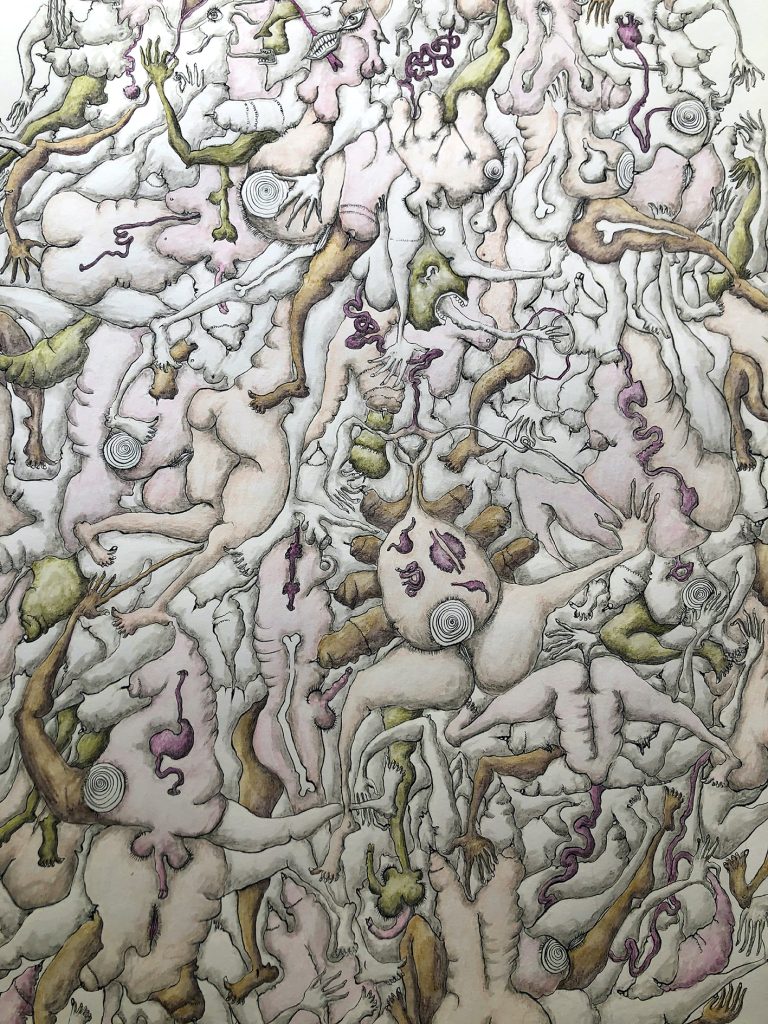

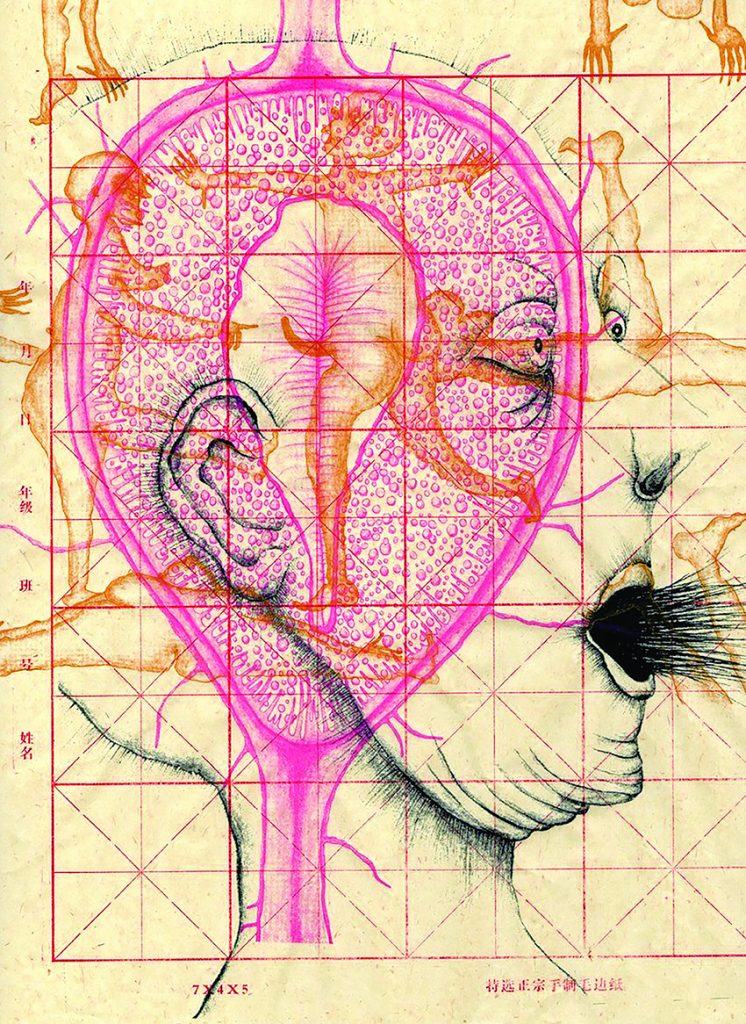

I often draw bits of bodies gone wrong – is this a direct influence from my experience of dissection at medical school, or was this interest for the inside of the body always there? What’s obvious is that I cannot get away from the body – it is in all my drawings even when I deliberately set out not to draw it , it just keeps coming back.

For me the body is a carrier of meaning for human vulnerability and ephemerality, sexuality and identity. I am also interested in

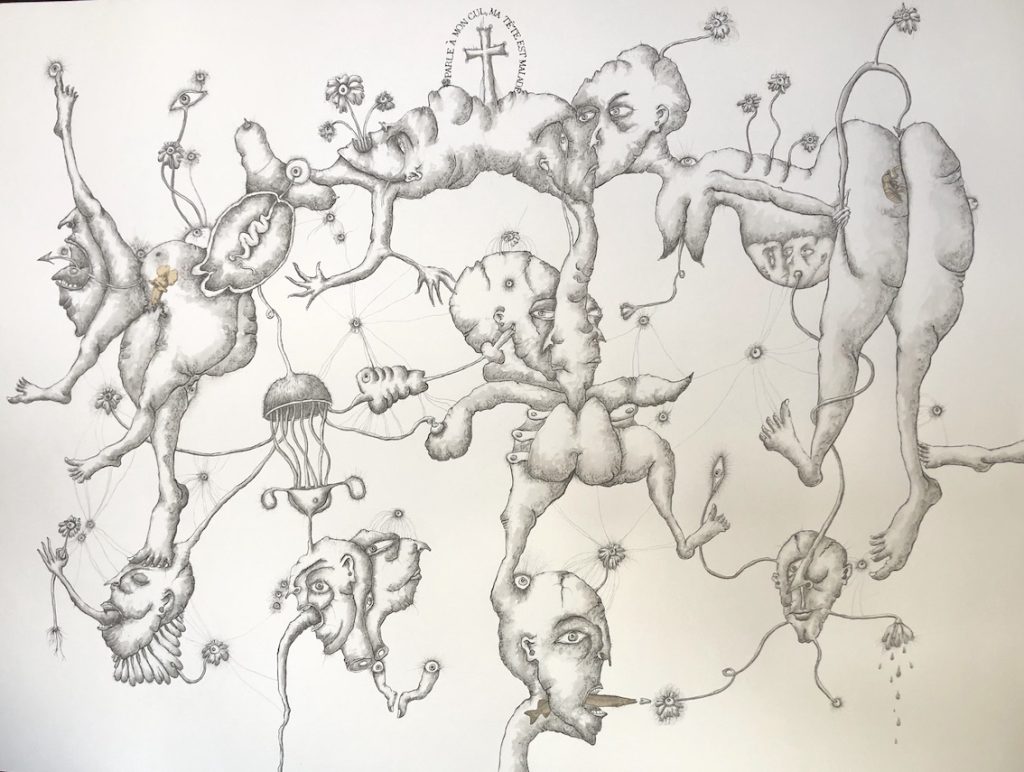

the history of medicine, especially historical Every day since 2016, parallel to my dorms of ‘madness’ and its physical manifestations such as the ‘wandering womb’ of hysteria, or excess black bile causing melancholy according to humoral theories.

I’m really interested in the inside of the body, the organs but also the mind. My dad was a hunter and a fisherman, so during my child- hood I would see animals plucked, gutted, butchered, and this has also influenced me I think and still fascinates me today.

Can you tell us more about your everyday drawing activity and how it serves as a foundation for your alternative forms of expression such as walldrawing, embroidered photos, and knitting installations?

ly work, I have made one drawing in small secret notebooks which also contain written notes and which I carry around with me all the time.

There are 2 aspects to this activity : firstly the actual ‘doing it’, the dedicated activity of drawing every day, whatever happens. This evokes the Latin phrase “Nulla dies sine linea” (meaning “no day without a line”), first used by Pliny the Elder about the Greek painter Apelles, who did not go a day with- out drawing at least one line. For me this is a defining activity of artistic life and a part of my artistic persona I suppose : it is what I do and who I am.

Secondly, these little drawings constitute a more generally of what I believe it is to be

In this way my drawing practice is about

‘reservoir’ of ideas, of source materials for further drawings. Because the notebooks are private, secret spaces (they include bribes of intimate texts much like a diary and I never show them to anyone), they allow for freedom and experimentation. The drawings made here form the basis for all my other drawing practices – I draw from them, rework them through processes of expansion, translation and repetition, often returning to older sketches to rework ideas. The delay between the diary drawing and its reworking often allows for growth into something else, where one drawing informs the next.

Drawing is described as “intimate, fragile, nomadic, subversive when enigmatic, experimental, immediate, secret, and underground” in your biography. Could you elaborate on what these qualities mean to you in the context of your art?

For me, these qualities make of drawing the medium of freedom and resistance essential elements of my work and an artist.

What I love about drawing is that it accom- panies me everywhere and all the time, all I need is some paper and a pen or pencil. This makes it a very cheap way of work- ing, an important element for me. I would compare drawing to making bread – with some very simple ingredients you can make something quite lovely.

There is an inherent fragility and ‘delicacy’ to these small works on paper – they allure and entice, they make you draw close and attract you into an intimate space. This idea of intimacy is very important to me : everything today is ‘on show’, in a kind of race to the most spectacular – counter to this I prefer to make small, intimate pieces, hidden work done deeply and slowly. Following An- nie Le Brun’s thinking about “a uglification of the world… which insidiously modifies our interior landscapes” and “the power of beauty as an escape route”, I aim to tap into a beauty that comes from down below, or inside, or underground.

creative resistance : a slowly but surely way of defying the everyday through a creative act (much like Penelope did and undid her weaving to avoid her fate and give her time to think). For me this takes the form of “(with)drawing” : drawing to the point of withdrawing, retreating as an oblique form of subversion and striving to make, live and think otherwise.

You’ve exhibited your work both in the UK and internationally since 2004. How have these experiences shaped your artistic journey and perspective?

If I’m honest, I would happily just stay in my studio and draw all day every day and never have to show my work in exhibitions! However, I do also feel that an artist has responsibilities and one of these is to share/ show their work. I feel constantly drawn between this need to show and a desire to hide, and I think I try to unravel this tension by producing enigmatic images and narratives, often mingled with a dark humour.

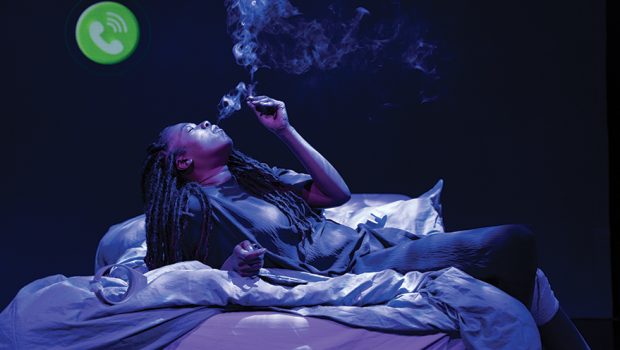

Collaborating with writer and theatre-maker Annie George for ‘Twa’ sounds fascinating. How did the animated drawings and live drawing during performances enhance the storytelling process?

Annie and I met during an artist residency (Rough Mix by Magnetic North), and during those 2 weeks we worked together but also lived together, and a real artistic friendship was forged. I still lived in France then so we began exchanging by email, a back-and- forth of thoughts around art and identity,

myth and using the creative act as a form of resistance, but also a more personal con- versation.

From this we developed the idea of ‘Twa’ which premiered at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2018. It’s a theatre piece which incorporates projected animated drawings and live drawing on stage during each performance. The process of collaboration involved me responding to Annie’s text while she gained inspiration from my drawings, and so the drawings are not an illustration of the text,

but rather the result of this process of back- and-forth between us : ‘Twa’ means ‘two’ in Scots. It’s a double storytelling, each in our own medium and with our own perspectives but coming together around common ideas and feelings.

Your residencies and bursaries have allowed you to explore new techniques such as etching and screen- printing. How have these experiences expanded your artistic repertoire and influenced your recent work?

In 2019/20 I was lucky enough to receive a Royal Scottish Academy Residency Award and an Edinburgh Council Emerging Artist Award.

With the RSA award I spent a year at Edinburgh Printmakers learning to etch, and exploring connections between this technique and my drawing practice, and notably through the use of repeated very fine, wiry lines, or ‘écheveaux’. I’m always striving for an ever-finer line and with etching I enjoyed the physical gesture of scratching, scraping the lines as a way of marking the surface, of “etching a little bit of life out of the blackness” (Louise Bourgeois). Bringing together drawing and etching also allowed me to make ‘unique prints’, by reworking each print with hand additions. I was also interested in the inherent reversal involved in printing as a metaphor for opposites and dualities, themes I explore in my work (particularly in relation to my double/split identity, between Scottish and French origins and languages).

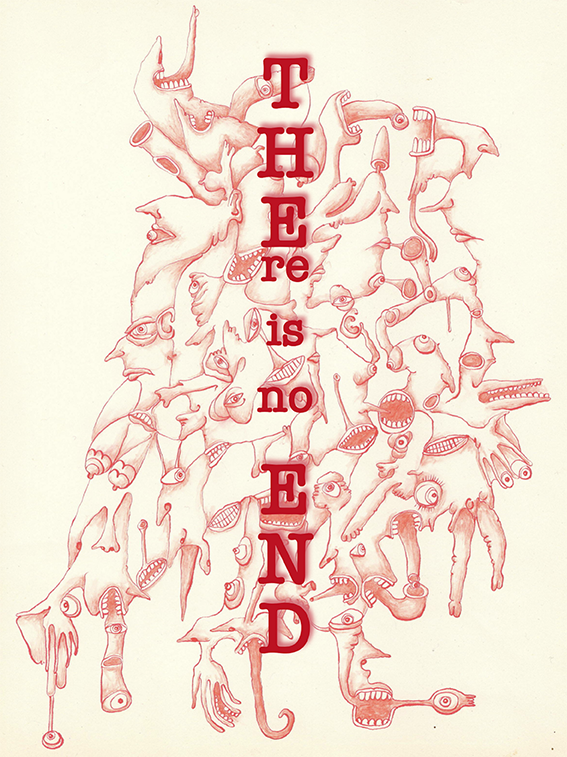

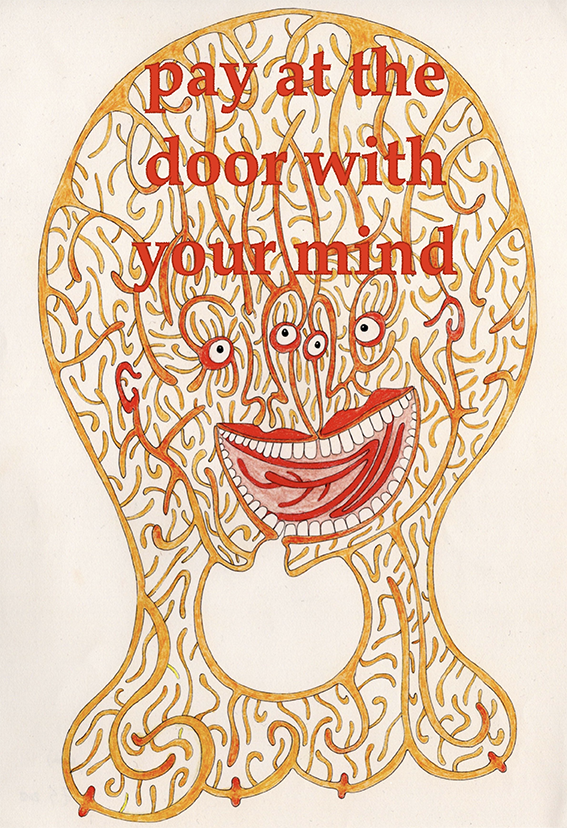

With the EC award, I learned to screen-print and this helped in bringing together my drawing and writing practices, notably through the idea of the printed multiple as a form of self-publication.

Your project funded by Creative Scotland focused on exploring connections between drawing and writing, resulting in the production of small printed multiples. What inspired this exploration, and what did you hope to achieve with it?

Reading and writing have always been an important part of my practice, but I wasn’t sure how to integrate these into my drawing practice. As part of this project, I did an experimental writing course at Edinburgh University (run by the brilliant Nicki Melville) and I suppose this gave me ‘permission’ to use my writing in combination with my drawing.

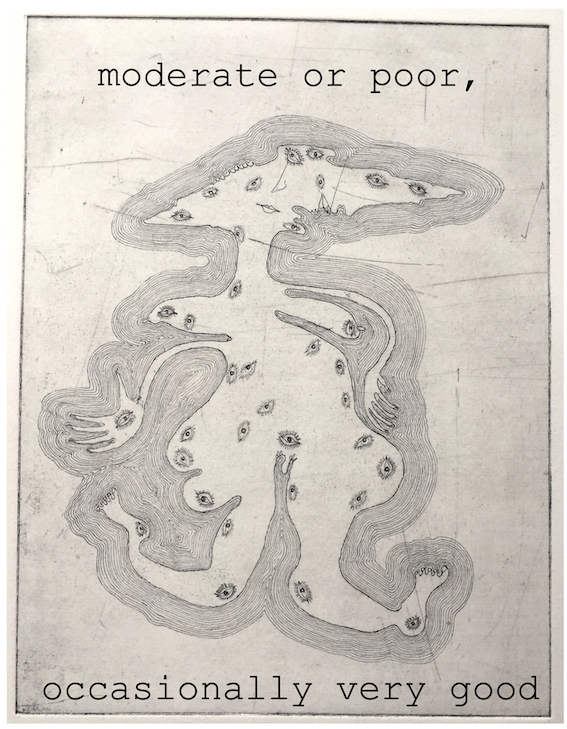

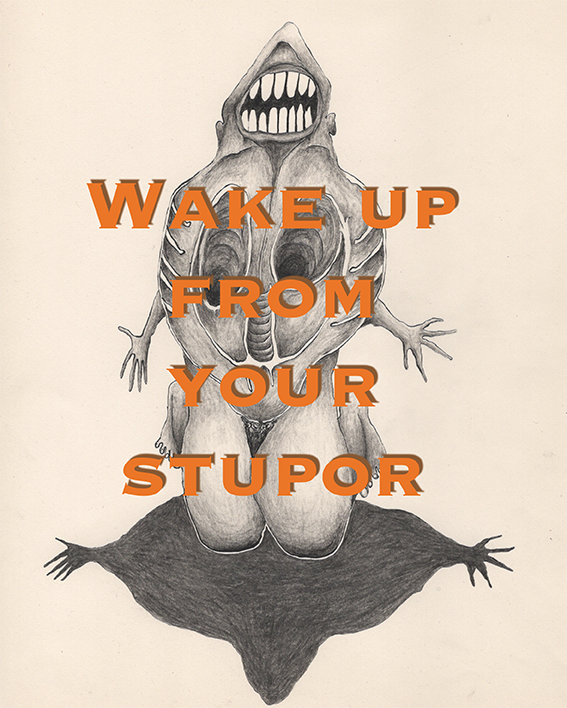

Notably I developed a project to create a series of printed multiples which each combined one strange drawing with one obscure short found-text in the form of a ‘slogorne’, a kind of anti-slogan. I wanted to subvert the normal use of slogan (as the repetitive expression of a political idea or marketing tool) towards something much more enigmatic, using ambiguous, evocative text. They could be described as ‘slogans gone wrong’ for instead of reinforcing an idea they are snippets out of which meaning needs to be found/ thought.

These printed multiples aimed to be obliquely subversive, to arouse curiosity and open the imagination. In a DIY spirit, I home-printed, self-published and distributed these for free in everyday alternative spaces in my local area with the aim of reaching wider audiences.

For me this is a way of having a greater connection between art and everyday life and connects to the concept of creative resistance. I would like these prints to be at once intimate and political, personal and collective (‘micropolitical) – a marginal, alternative form of art.

Currently, you’re part of the Drawing Correspondence program ‘Shadowlands’, delving into ideas of obscurity and the underground in relation to prehistoric cave drawings. Can you share more about your research and how it’s shaping your artistic practice?

Faced with the prospect of my own death (after a diagnosis of aggressive breast can- cer last year) I feel the need to see, explore, confront what must be considered the birth of art and of the ‘human’, maybe in a desire to put things into some kind of perspective. Recently I visited the caves in Chauvet and I was struck by the delicacy and the feel- ing of closeness of these drawings despite

their extreme temporal remoteness. It is mind-boggling to think that 30,000 years separate these marks from the marks I make every day in my studio.

At least some of these cave paintings were made not to be seen (since they are found in the deepest of recesses, where it is difficult to reach), and so what was their purpose? Was the making more important than the result (like the art of many ‘outsiders’ and something which resonates with my own practice)? Was there also just a desire to mark the wall (like the urge we sometimes feel to mark, scratch, scribble)? Were they part of some secret ritual which had to be hidden in a dark place?

There is a bareness to these prehistoric markings that seems to let us glimpse into what is ‘essentially’ human, and we some- how recognise ourselves in these the most remote of images. They allow us to see in- side the human for the first time ever and the feeling is one of uncanniness – deeply, strangely familiar.

From this research, my new project consists of the creation of a large-scale drawing along one horizontal line, which rep- resents the limit between the realm of the underground (dark, unseen, unconscious) and what is above (growth towards the sun, vision) : drawing is situated in/on this

in-between, as is the cave. This monumental drawing would be based, once again, on my small secret drawings made in my notebooks, and would form an ‘inscape’, that is an inner landscape of the mind.

How do you navigate the balance between traditional drawing techniques and the more experimental aspects of your practice, such as live drawing in theatre or creating interactive installations?

I think my daily drawing practice on paper is the core of my practice, and actually it’s there that the most experimentation takes place. Sometimes I branch out but really it’s always an exploration of drawing, be it in its expanded field. Often these other aspects, such as drawing live on stage, push me out of my comfort zone, challenge me and my practice, and are experiences in collaboration, but I always return to drawing. Just like Sisyphus’s rock is his thing, drawing is my thing

What advice would you give to emerging artists looking to carve out their own unique path in the art world, especially those interested in exploring interdisciplinary approaches like yours?

Be brave. Make the work you want to make, paying no attention to fashion or what anyone tells you you should make. This quote from Ali Smith, « a picture… at the seeing of and liking so much of which she literally stopped being sad » describes exactly why I draw – I’m just trying to make that picture. And how lucky I am that every morning I get up with the same urge to work.