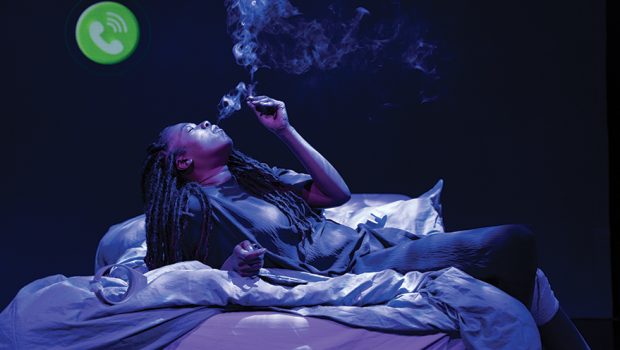

Dream on!

''A dream is a microphone through which we look at the hidden occurences in our soul"

By David Schembri

One of the most intriguing phenomena of human existence is dreaming. Dreams, since time immemorial, have enabled human beings over the years to go through journeys in inexistent lands, and live through experiences which have not been lived.

For centuries, these insights into this “other dimension”, so to speak, which often feel real, have scared, confused, intrigued and excited those who have experienced them. Needless to say, a variety of interpretations for this phenomenon abound, starting from the mythological musings of earlier civilisations to the philosophical pondering of later generations and on to neuroscientific studies carried out in these past years.

In the beginning was the dream – at least according to Australian Aboriginal mythology. In this tradition, the Dreamtime is the period of time in which the world, men, women and the laws they had to obey were created. In some Aboriginal cultures, the Dreamtime is still going on but hidden; in others, the Dreamtime is now over. The connections to the supernatural are also present in other cultures, particularly in the Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

One particular dream stands out as being particularly significant to these traditions, and that is the dream where Jacob dreamed “there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven”, with “the angels of God ascending and descending on it”. In this dream, God promises Jacob who was later to become Israel –to give the land he lay on to him and his descendants, who “shall be like the dust of the earth”, scattered all round the world. That’s one dream that came true.

Still in the Bible, in the book of Daniel, the prophet interprets the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, which in turn won him favour with the king. Interestingly, Daniel came to know of the content of the dream not through Nebuchadnezzar himself, but through a vision from God in the night. God is also seen as giving instructions through dreams: Joseph, the husband of Mary, is instructed by an angel in a dream to flee to Egypt.

But the prophetic nature of dreams is not exclusive to the Abrahamic religions. The Mesopotamians believed dreams carried omens, as did the ancient Greeks, who had a designated god – Morpheus – to appear in dreams (later to star in The Matrix trilogy). The ethereal nature of dreams is also captured vividly in the indigenous North American tradition of dream-catchers –elaborate nets which were placed over beds to filter the bad dreams and keep the good ones in.

Nowadays, rather than being a window onto the spiritual realm, dreams are more often seen as being a window into our subconscious. Although it is more prevalent nowadays, the roots of this theory stretch deep into history, at least back to the time of the Upanishads (900-500 BC), a set of Indian philosophic texts, where dreams are seen as yet another mode of consciousness, no less real than our waking state.

The link between dreams and the subconscious is most often connected with Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. In his classic work The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud dismissed the notion of dreams as being nonsensical; rather, he calls the interpretation of dreams the “royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind”. Freud saw dreams as manifestations of unconscious “wish fulfilment’, which, if read between the lines, would be related to memories and experiences from our early childhood.

Carl Jung, while rejecting many of Freud’s theories, did agree with him on one cardinal point: namely that dreams are manifestations of our unconscious self. He placed a large amount of significance on dreams, eventually coming to believe that dreams were a form of message to the dreamer, with repeated and recurring dreams being considered a form of unresolved business to which one must attend.

A person’s concerns and state of mind are also an important factor when it comes to dreams. A recent study centered on divorced people found that the ex-spouse featured more often in the dreams of the subject for whom the divorce was still an issue, with the former partner featuring less and less in the dreams of those who were getting over their divorce.

In a similar vein, people who have been through trauma and who experience fear in real life often have a higher incidence of nightmares and anxiety dreams – further proof, if any was required, of the intimate relationship which exists between our dreaming and waking selves.

These findings are perhaps a more articulate understanding of long-known truths. For instance, in the most ancient of Buddhist texts, the Pali Canon, we find that the man centered in loving-kindness “sleeps easily, wakes easily, dreams no evil dreams”.

This relationship between dreamed and dreamer is also expounded by neurology. Eugene Tarnow, for instance, re-jigs Freud’s theories and posits that dreams are the “excitation” of our long-term memory, which in turn explains their strangeness. Furthermore, other neurological studies suggest that the illogical locations, characters and dream flow may actually strengthen and link what are known as semantic memories.

Meanwhile, science has indeed acknowledged the fact that some dreams foretell our future. What it also says is that, more than a window into the future, it is our memory being selective and remembering only the dreams that were actually reflected

in real life.

Then again – in the tradition of Rene Descartes and The Matrix – who is to say that “real life” isn’t actually a dream in itself?