Artists in a disturbed society

KSU student Stephanie Bonnici on the body as a medium in performance art

Words: Stephanie Bonnici

Defining performance art has been problematic for both artist and spectator ever since its emergence in the second half of the 20th century. Frequently, performance art has been associated with controversy and censorship, and has very often been regarded and criticised as to being gratuitous and bizarre. Art historian RoseLee Goldberg writes: ‘Historically, performance art has been a medium that challenges and violates borders between disciplines and genders, between private and public, and between everyday life and art, and that follows no rules.’ The context of the 1950s and the decades that followed, in which performance art originated, is a clear indication of such assumptions.

In light of the social upheavals happening at the time, namely the fight for female equality, sexual freedom, civil rights and the fight against the unfair treatment of races, the body took on an important role as a medium with which artists created their work. Many artists regarded the use of the body as a means of expression, but also of questioning issues of gender. Artists sought ways of referring to and describing the various events happening at the time, through deliberate provocation and attempts to go against the conventions of past artistic traditions and values. Following World War II, performance became a useful medium for artists to explore the human existence in itself. The body had come to be regarded as a medium to communicate shared physical and emotional experience through direct human connection.

Performance art is interdisciplinary and consists of four elements: time, space, the performer’s body, and a relationship between the performer and the spectator. The artist’s medium is the body, and the live actions he or she performs are the work of art. Artists such as Kazuo Shiraga of the Japanese Gutai Group were inspired by Abstract Expressionism to emphasise the body’s role in artistic production, and made a sculpture by crawling through a pile of mud. In Paris, Georges Mathieu staged a similar performance where he violently threw paint at his canvas. The artist’s actions came to be regarded as equally important to the artwork produced.

Performance art very often leads audiences to think of issues in an uncomfortable manner, but also leads to the realisation of life’s absurdities and the peculiarities of human behaviour. Marina Abramović, who has been described as the ‘grandmother of performance art’, is the classic example of the lengths that performance artists allow their work to take them to. The artist often endangers herself by means of the lengthy and harmful routines which she creates and performs; making statements in a manner that has led to her being regarded as absurd and irrational. She believes in total immersion in her art, both on her own personal level, yet also in her viewers and spectators. She tests her own physical and mental limits, and has inflicted upon herself and endured cutting, burning, and privation, amongst other sacrificial forms, as many choose to regard these situations which she places herself in.

“The function of the artist in a disturbed society is to give awareness of the universe, to ask the right questions, and to elevate the mind.”

Abramović’s approach in her performances has often been regarded as a displacement of art directly on her body. Yet, she has stated that she thinks of the body as the ‘point of departure for any spiritual development’. In her groundbreaking work, ‘Art must be beautiful, artist must be beautiful’, she positions herself in front of a camera, directly addressing her viewers, revealing only her face and hands. She forcefully combs her hair, without a pause, for more than 50 minutes, repeating the sentence ‘art must be beautiful, artist must be beautiful’. Both artist and audience are put into a trance-like state by means of this performance-encounter, where overcoming the physical pain frees the body and mind from the conventions of Western society and culture.

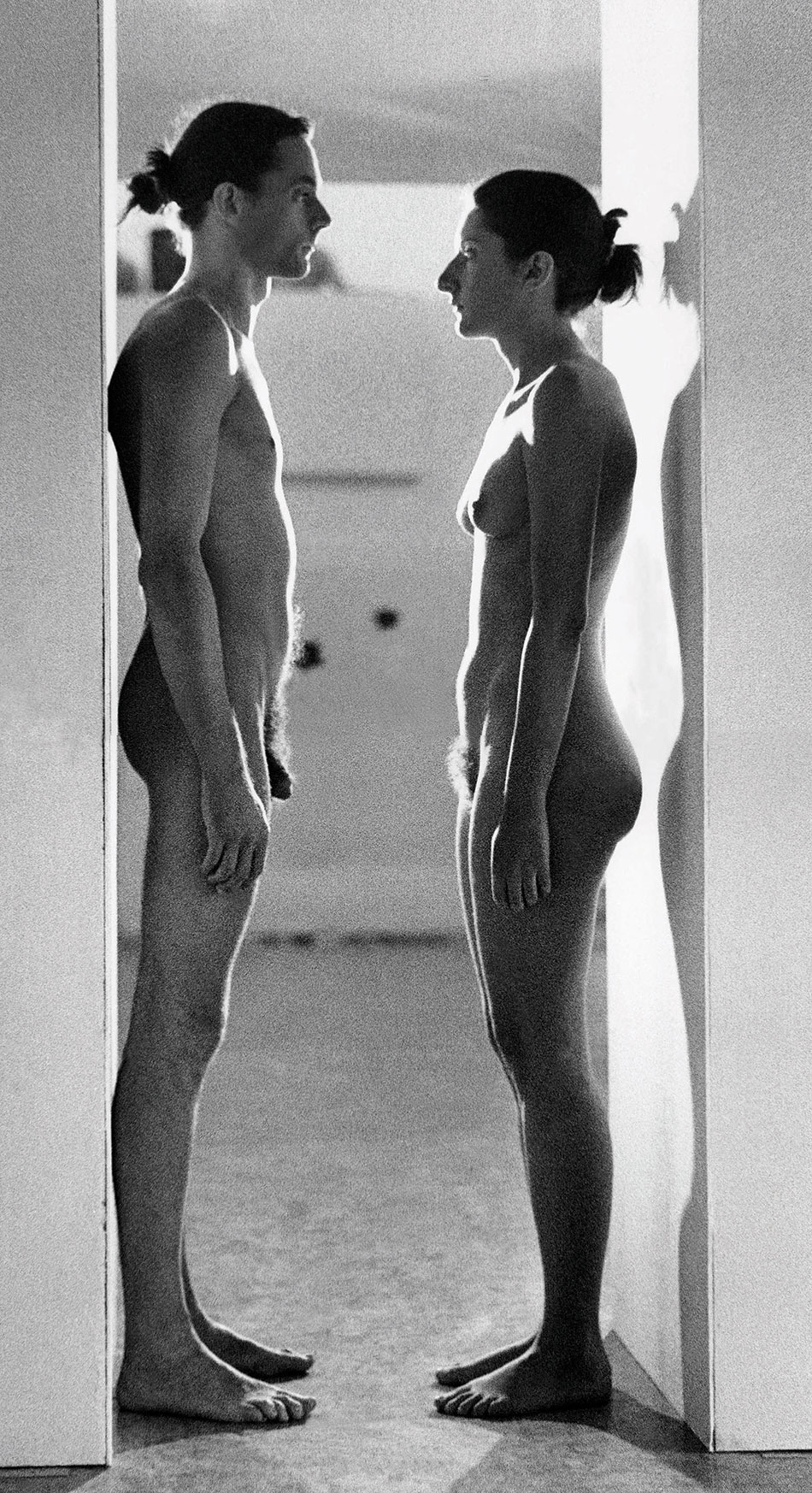

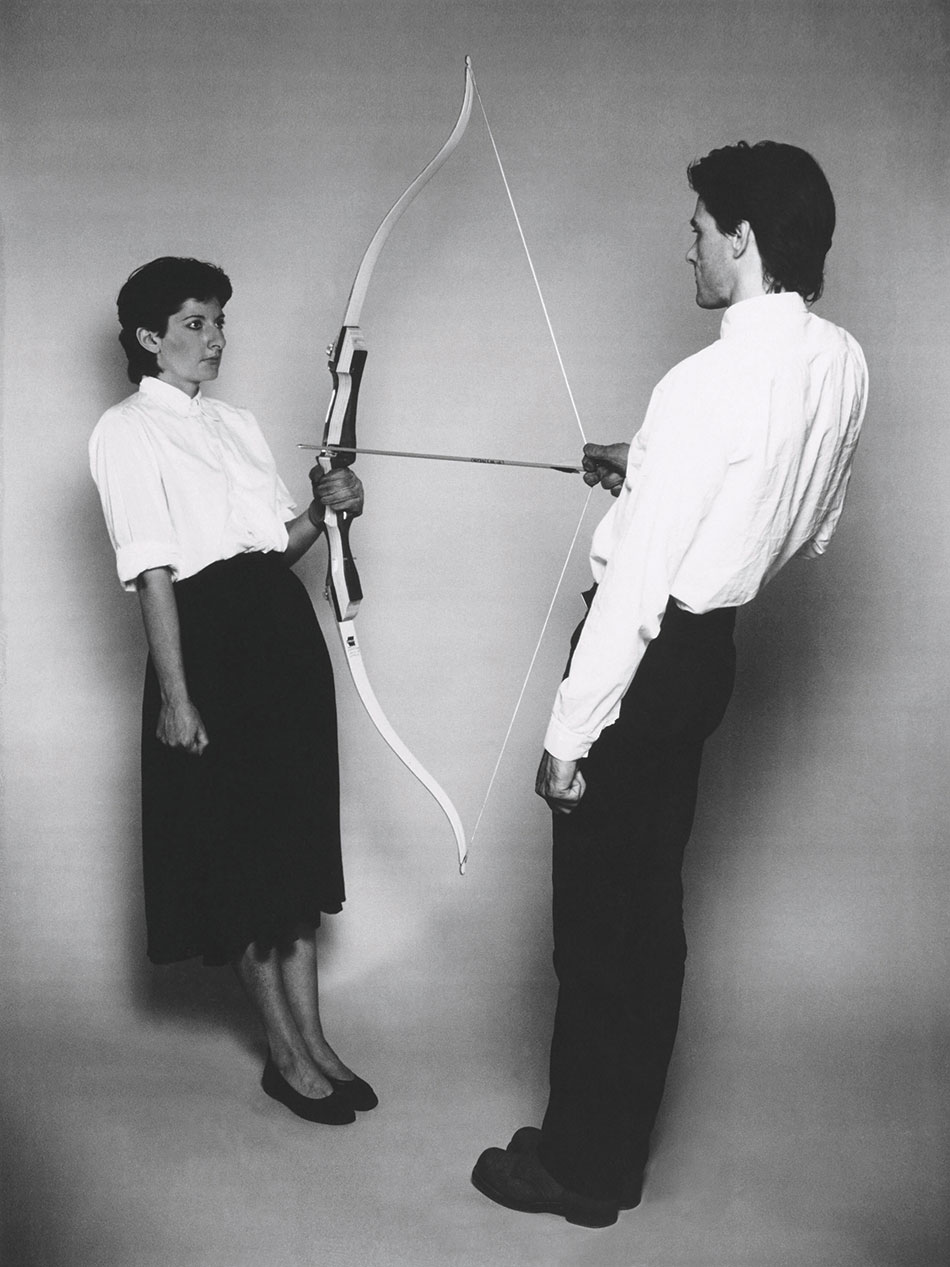

Some of Marina Abramovic’s more controversial work was created in collaboration with German artist, Ulay. The pair exploited their duality to investigate ideas such as the division between mind and body, and naturally, male and female. Their performance, Imponderabilia, involved them both standing naked at the entrance of the Museum of the Galleria d’Arte Moderna Bologna, opposite each other in such a way that people wishing to enter the museum, had to squeeze singly through the gap between the two, unable to avoid physical contact. Participants of this performance were confronted with the experience of touch, physical contact and the exposure of an unfamiliar bodily sensation.

The questions and implications that emerge from the artist’s bodily expression and challenging of social norms is a challenge that performance art confronts those who experience it. Whatever the outcome or impact, its history shows that it generates an art that is visually and viscerally, yet also mentally and physically challenging to its spectator.

“Performance art has been associated with controversy and censorship, and has very often been regarded and criticised as to being gratuitous and bizarre.”