Body Politic

Body parts and their personalities...

BY JULIAN CARDON

She hated American football with a passion. Rather girly and a lover of frills, she lived a life that was all pink and loving in a very cherubic kind of way. She likes people going head to head and smashing things up as they chase a football in a testosterone-drenched arena. She memorises all the players’ names and their field position; she enjoys screaming at the top of her lungs on the stands every Sunday afternoon and spewing navy-type curses all over her under-performing heroes.

The funny thing is that both of them are the same person: Julie Shambra.

It’s just a case of past and present; just a case of pre-kidney transplant operation and post.

When Julie met Nailah Karimah, the mother of 18-year-old Dakari Karimah, on a TV talk show, she made a startling discovery that sent shivers down her spine and brought her to tears. After Dakari had died, his kidney was transferred to Julie (who was dying due to severe diabetes), in a successful transplant operation in San Francisco. What Julie didn’t know was that her life would change dramatically. Her deep love for rough sports, her change in appetites and her new-found energy all possessed her in an inexplicable way and it almost seemed that she now became two people living inside one. Julie’s meeting with Dakari’s mother left her certain: part of Dakari was living inside her in more ways than simply physical. Nailah, the African-American mother, describes Julie and her son as “just a little colour difference, but other than that, they are just one little pillow pea in a pod.” She also explains how it seems that she has known Julie all her life as if they were “best friends forever”.

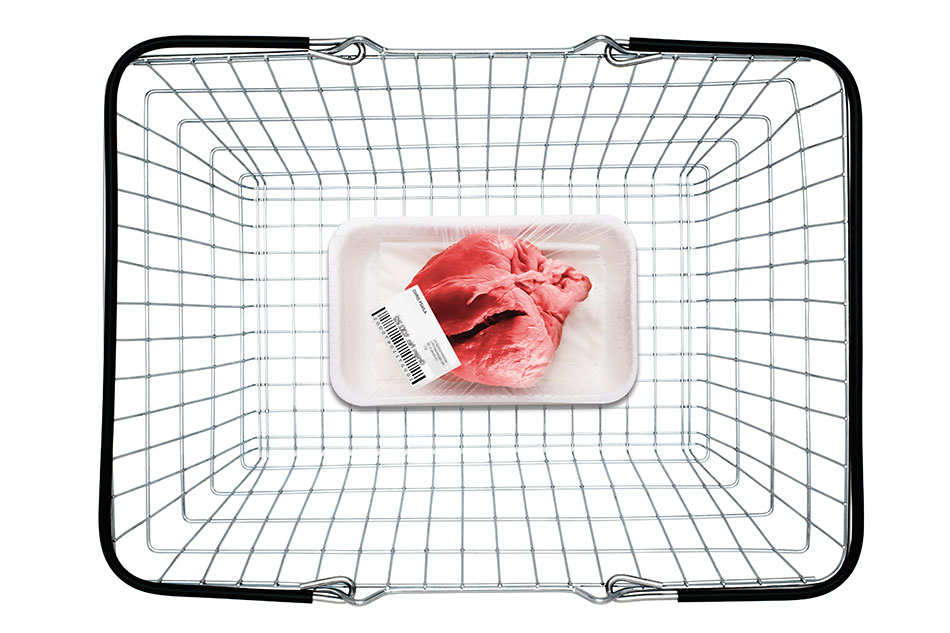

Research shows that the case of Julie and Dakari is not an isolated one. In fact, many people who receive organs from donors describe inexplicable changes in tastes and appetites, attitudes and temperaments, hobbies and passions and even life philosophies and ambitions. Perhaps the most startling case of all was that of an eight-year-old little girl who received a heart from a 10-year-old girl who had been brutally murdered. The dreams of the girl with the new heart were bombarded with explicit images of an attack, so explicit and detailed, in fact, that she was able to use her recurring dreams to help the authorities identify the murderer.

But can all of this make scientific sense? Because if it is all true it means that somehow organs have the capability to store information about a human being’s personality. We must remember that it is generally assumed that learning involves primarily the nervous system and secondarily the immune system. Hence, patients receiving peripheral organ transplants should not experience personality changes that parallel the personalities of donors they have never met. This does not seem to prevent it from happening, however.

Doctors have coined the term ‘Cellular Memory Phenomena’ (CMP) meaning that information could be codified inside every cell in the body and then passed on after the transplant. Even though there is little scientific evidence to support this, Arizona researcher Gary Schwartz has presented a theory stating that since every cell in the body contains a complete set of genetic material, transplant patients inherit DNA from their donors that determines, in part, how a person thinks, behaves and even eats. “Hearts can have memory, as brains do,” according to Schwartz. Many medical professionals say that this can only be science fiction and are critical of Schwartz’s findings, arguing that he based his theory on a study of just 10 transplant patients. Dr Tracy Stevens, medical director of the cardiac transplant programme at St Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, is adamant that “there is no evidence of clinical findings to suggest that cellular memory exists”.

…”People who receive organs from donors describe inexplicable changes in tastes and appetites, attitudes and temperaments,

hobbies and passions and even life philosophies and ambitions…”

More research has involved the study of neuropeptides. These provide a two-way communication channel between the brain and every organ, but no conclusion has yet been reached as to whether these circuits can actually store information in the organs as they do in the brain. If one were to assume that they can, this would explain the fact that the most astonishing changes happen when people receive a donated heart, as the heart is the organ that has the highest amount of neuropeptides.

But then the next obvious question is this: why doesn’t every organ receiver experience these much celebrated life changes? Some argue that it might be due to the fact that some organ receivers are not as “in tune” with their body as others might be. Schwartz goes further than this. He theorises that organ rejection might happen on two different levels: a physical level, meaning that the body does not accept the material comprising the cells, but also at an energy level, that is, the body might also reject the systematic information and energy stored in the cells of the peripheral organ received. All of this is thus far neither proven nor rejected, even as life-changing cases continue to crowd inside medical journals.

There is no doubt that Julie and many like her would dismiss the sceptics. Their experience is tangible and anyone who shares a life with them can testify to this. If future medical research confirms what people like Julie know to be irrefutable, then the implications could be vast, especially when it comes to body-mind problems that have occupied philosophers since Plato and Aristotle. It could shed light on questions about the soul. Are we really a soul caged in a body or are we simply a bunch of genetic codes that subsists not only through our spirit and consciousness but also through our vital organ? On a less spectacular note (or perhaps even more spectacular) girls could smile when hearing the true story of that very lucky girl whose boyfriend became a shopaholic after he received the heart of a young woman. Just imagine…