I wanna be a rock star

An examination of the time we stop reaching for the stars and hit “The Crisis”

Words: Lisa Borain

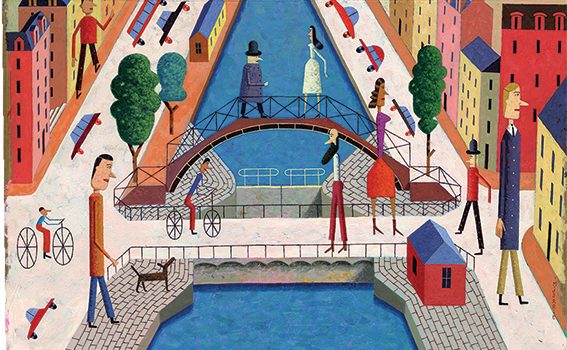

Youth brought most of us the solid confidence that we would be rich, famous, and desired by all. We wanted to be rock stars, Formula 1 race-car driving champions, best-selling novelists, famous footballers and ballerinas, platinum album-selling singers, and super star actors.

Most parents discouraged the famous thing – and maybe not wrongly so. It’s extremely difficult to work out the exact percentage of famous people on the planet, but an approximate ratio is somewhere between about 1 in 10,000 and 5 in 10,000. This ratio feels like it makes it safe to say that there aren’t that many notorious people in the world.

When we were kids, we weren’t good at differentiating between being “rich and famous” and following our dream. And perhaps neither were our parents.

Likely stemmed from their emotionally protective fear of our own possible disappointment, we were encouraged to aim lower. We were taught to be sensible. As a result, the vast majority of us stopped thinking about reaching for the stars. The rich and famous dream lasted longer for some than others. Some of us pursued higher education in the field of our choice to get closer to the ultimate dream, but began to understand that the one degree of separation percentage to the handful of famous people in the world was (slowly un)surprisingly low. Our parents were right.

Novelist Paolo Coelho nails it: “We are told from childhood onward that everything we want to do is impossible. We grow up with this idea, and as the years accumulate, so too do the layers of prejudice, fear and guilt. There comes a time when our personal calling is so deeply buried in our soul as to be invisible. But know that it’s still there.”

There comes a point when the first realisation hits that we are not going to be rich, famous, or desired by all. Then the second realisation; we might not even actually be above average in our career, financial disposition, or relationship.

It’s probable that a lot of us ignore these sparks of reality along the way until it hits us all at once and suddenly. In a philosophical paper written by the psychoanalyst Elliot Jaques in 1965, a hypothesis was made that a crisis occurs when a midlife adult begins to come to grips with mortality, realising that he or she won’t be able to fulfil all the dreams of youth. The notion was dubbed a “midlife crisis”. As the concept began to evolve, it became associated with a host of other problems that become more noticeable during midlife, such as relationship difficulties, trouble with children, and career despair.

Studies have now found that this “crisis” is shown to start much earlier, probably linked to younger people beginning their careers earlier – which means that it’s no longer apt to be called a midlife crisis.

When experiencing this crisis, people begin to reassess their achievements in terms of their dreams. The result may be a desire to make significant changes in various areas of their lives, some positive, others negative. Studies have shown that a common reaction to the situation is for people to begin comparing themselves to their peers for orientation, the result of which can – for obvious reasons – be hugely unhealthy and unhelpful.

The comparison of where we are in life largely depends on standards. If living in a country where rife poverty is a reality, it’s easier to put things into realistic perspective and feel better about not reaching the desired point in a career. If people are subject to disease and early death, it’s a lot harder to feel inferior for not being able to afford travel or acquire a new car. Malta happens to be tough crowd, with its extremely high world ranking (number 15) in the home ownership scale, with 80.3% of people owning their own homes. Malta also has the lowest overcrowding rates for those at risk of poverty. Only after Cyprus and Ireland in the EU (both 4.9%), Malta has a 6.3% overcrowding rate. The unemployment rate is at a mere 6.4%. As a result, the general standard of comparison is relatively high.

As for the famous part of the rich and famous dream, according to Psychologist Donna Rockwell, “so many people in our culture clamour at some level for their own slice of fame, first noted in Andy Warhol’s prediction of 15 minutes for everyone… In fact, iconic filmmaker Jon Waters believes that being famous is everyone’s unspoken desire. ‘Most everybody secretly imagines themselves in show business,’ he says, ‘and every day on their way to work, they’re a little bit depressed because they’re not… People are sad they’re not famous…’.

“The relevant question becomes how can a celebrity survive fame? How can someone take a God-given talent… rise to mega-stardom, and ride the merry-go-round of fame with health, grace, and perspective until it is time to finally get off? Clues to the answer lie in becoming part of something larger than oneself (countering fame’s natural tendency toward narcissism), and dedicating all one’s drives and ambitions into making a real difference, in a meaningful way, in the world.”

What if we finally differentiated between the dream and fame?

Research conducted by Dr. Susan Krauss Whitbourne showed that people who changed jobs before their midlife years had a greater sense of generativity when they reached mid-life. They also experienced a greater sense of motivation to deviate from stagnation and a desire to help the younger generation thrive.

Psychologist Erik Erikson used the term “generativity” to capture the need for all of us to leave something behind for future generations. The opposite of generativity is stagnation, in which we put our energy into focusing on ourselves rather than into helping others. It’s been said that generativity can help our personality flourish, even while we provide vital support to the next generation. Stagnation carries the risk that potential growth can turn inward, and possibly disappear altogether. This is not the same as becoming a parent, as having children offers no guarantee of generativity. Turning our own experience into life lessons can help inspire others to be more conscientious. By helping others, whether our own children or other younger people, we’re also enhancing our own psychological health. Researchers interested in generative behaviours are producing studies that people high in this personality quality are more likely to engage in acts that do benefit their communities, both now and in the future.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. University of Dayton psychologist Jack Bauer (not the 24 Jack Bauer; the surname derives from Germany, meaning “farmer”, so very common), proposes that people high in generativity have another alluring personal quality dubbed the “quiet ego”. In psychological terms, a noisy ego is said to vie for attention, always on the look-out for fame and recognition. Generativity kills the desire for an enhancement of our own sense of self and a greater tendency for an ego to take a back seat to the needs of others.

“This is a tremendous step in development, allowing you to bask in the accomplishments of the young without feeling that your own self-worth is being threatened.”

Back to Erikson. His thought was that “with stagnation, middle-aged adults increasingly experience feelings of disgust and disappointment with the young, leading them to become alienated and eventually cut off from more and more people around them. As they do, they also become cut off from their own identities”.

Many of us will remember from our basic psychology classes that Erikson believed that each stage of life builds on the next. By that rationale, if we are able to establish a firm sense of generativity, that belief in leaving a lasting legacy will cushion the changes of the coming years when we think about the larger meaning of our lives.

So maybe it’s not too late. Maybe we shouldn’t be giving up on the dream, but rather understand that it’s not riches and fame we’re truly dreaming about. How can we possibly be disillusioned with life if we know that we’re a part of the positive development of the world, pursuing our callings with the ultimate aim to share them, rather than simply be famous? Now that sort of ever-evolving immortality seems more like living the dream ought to be.