Inside the mind of Martin Jarrie

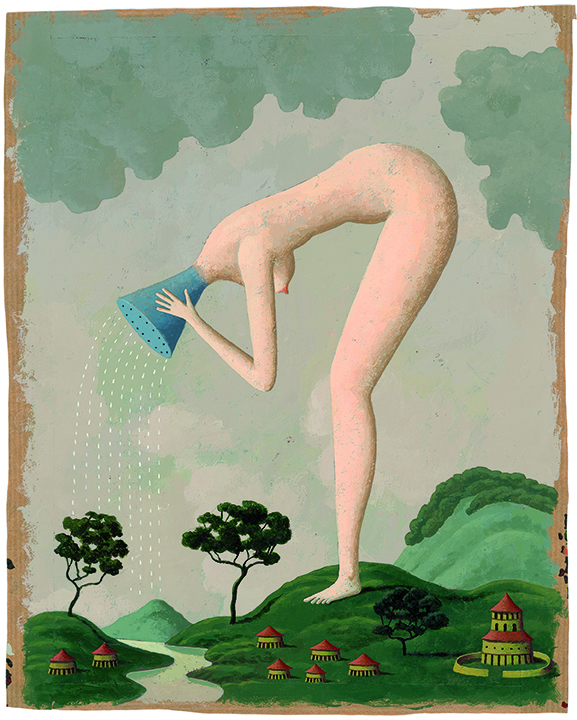

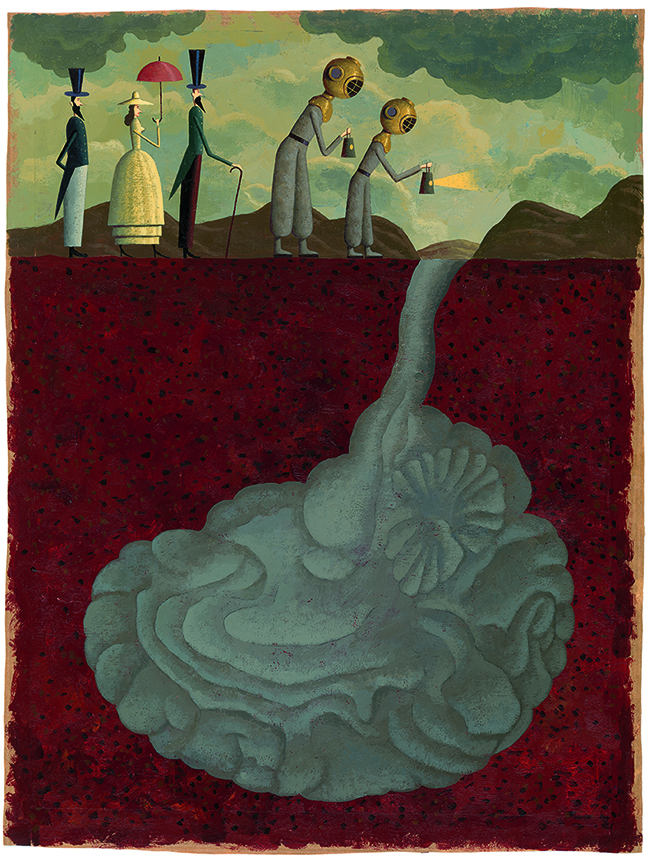

Martin Jarrie, a renowned French artist and illustrator, has captivated audiences for over four decades with his eclectic and evolving style. Beginning his career in Paris with hyper realistic drawings for advertising, Jarrie soon transitioned to a more personal and expressive approach influenced by masters like Giotto, Matisse, and Robert Zakanitch. His work, enriched by elements of surrealism, Italian primitives, and outsider art, has garnered prestigious awards such as the Grand Prix at the Biennial of Bratislava and the Best Album Award at the Montreuil Children’s Book Fair. Jarrie’s art, celebrated for its inventiveness, humour, and sensuality, continues to inspire and delight a global audience. Vamp caught up with the artist to find out more

Could you talk to us about your journey as an artist, from your beginnings in Paris to your current style?

When I arrived in Paris, my portfolio consisted of hyperrealistic drawings and the trend in advertising was also hyperrealism, so I started with advertising commissions in this style. I also quickly began illustrating children’s books for Gallimard in a more documentary style. This lasted for ten years. However, I soon felt the urge to draw and paint in a more personal style, influenced by painters like Giotto, Matisse, and an American painter, Robert Zakanitch – very eclectic influences.

In 1991, I decided to present a more personal portfolio to my agent and took on a pseudonym. This was very decisive, and I felt like I had a second creative birth! Then, my style asserted itself and evolved, changing over time. I think that now, my style has been enriched by the multiple layers traversed over all these years, from the realism of the beginnings to the childlike joy I rediscovered later by changing style and name.

Have you ever encountered an unexpected element that influenced your work?

I think of discovering this American painter, Robert Zakanitch, during a vacation in the south of France in 1983. He exhibited very large canvases full of sensuality in the subjects – fruits, flowers, animals – and in his way of painting with thick, generous strokes on the canvas. This impressed me greatly and was a kind of revelation at the time, even though I didn’t follow that path afterward.

What does being a successful artist mean to you?

I don’t know what that means; in any case, it doesn’t apply to me. I am a painter and illustrator who has lived off his work for 43 years, and that is my main “success.”

How do surrealism, Italian primitives, outsider art, and contemporary art manifest in your work?

These are movements and artistic expressions that have greatly nourished me for decades. I love the collages and juxtapositions in surrealism, “like the chance encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella,” as Lautréamont said. In Italian primitives, I was struck by the harmony of colors and perspective in Giotto, and in outsider art and contemporary art, the use of materials other than paint, such as wood, fabric, wax, etc.

Which contemporary artists inspire you and why?

Many contemporary artists inspire me. I think of Eduardo Arroyo for the composition of canvases in panels that interact with each other. I think of Jean-Pierre Pince- min for his work between abstraction and figuration and his painterly touch. I think of Martin Assig for his compositions and color palette. I think of Vincent Bioulès for his landscape paintings, and I think of David Hockney for his childlike joy of painting.

How have awards from groups like Communication Arts and the Society of Illustrators impacted your career?

These awards, which I was pleased to receive, did not impact my career. However, some prizes received in France and Europe had an impact. I am particularly thinking of the Grand Prix at the Biennial of Bratisla- va in 1997 and the Best Album Award received in 2002 at the Children’s Book Fair in Montreuil near Paris. These were both somewhat challenging books for children, and they allowed me to continue on this difficult and demanding path.

How do you balance your artistic vision with the demands of commercial projects?

It has always been difficult to achieve a balance. To be honest, I have always struggled to incorporate artistic elements into commercial projects, with very, very, very rare exceptions. The constraints are too great, and I have rarely had the talent or opportunity to marry the two. Now, I only accept projects where I feel I will have freedom, at least the freedom to have fun.

Can you discuss the creative process behind your award-winning works “The Mechanical Colossus” and “Knock, Knock, Mr. Cric-Crac!”?

These are two very different projects. In the case of “Knock, Knock, Mr. Cric-Crac!,” it was about illustrating a funny and meaningful text by Alain Serres. It was the first album I was asked to illustrate, and it was an opportunity for me to develop a kind of graphic code (houses, characters, objects), and it was a great pleasure and almost like a game.

For “The Mechanical Colossus,” it’s a whole different story. Following a visit to an exhibition of 18th-century engravings by Gautier d’Agoty at the National Library in Paris, I wanted to create large drawings and paintings of imaginary anatomy. I made about thirty of them, as well as sculptures.

This collection was exhibited at the Montreuil Children’s Book Fair near Paris in 1996, and the director of the fair and the director of Editions Nathan decided to make it into a book with texts by Michel Chaillou. I believe that’s what drove me to draw these imaginary anatomies was the mystery of inhabiting a body and proceeding with these paintings as in a voodoo ritual or, like in Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” the secret and illusory hope of creating life. There was something very intoxicating in creating these paintings.

What inspired your projects “The Fabulous Alphabet” and “A Big Kitchen Like a Garden”?

For “The Fabulous Alphabet,” my childhood love for dictionaries and encyclopedias made me want to create this picture book. Starting from real and sometimes very

rare quotes found in various dictionaries,

I wanted to translate them into intriguing, surreal, or naive images. As for “A Big Kitchen Like a Garden,” I have been paint- ing fruits and vegetables for a very long time (perhaps a memory of my father’s garden). I had many of these paintings in my studio, and a publisher, Alain Serres, suggested using them to illustrate a cook- book.

What impact do you hope your art will have on viewers or society?

I hope that my work can make people happy and inspire them to create, as it did for me when I discovered and continue to discover certain painters and artists. That would be wonderful! As for having an impact on society, that seems illusory to me.

What do you want people to take away from your art?

Inventiveness, humour, the pleasure of discovery, and a certain sensuality.

How do you balance art as self-expression with art as a product?

I don’t see art as a product. Of course, I am happy to be able to sell my works to make a living, but I don’t think about that when I create a painting, drawing, or sculpture.

What motivates you and makes you creative as an artist?

It gives me a reason to live and not constantly think about my mortality. It’s my oxygen and nourishment; it keeps me moving forward in life and often allows me to connect with others despite being very solitary.

rare quotes found in various dictionaries, I wanted to translate them into intriguing, surreal, or naive images. As for “A Big Kitchen Like a Garden,” I have been painting fruits and vegetables for a very long time (perhaps a memory of my father’s garden). I had many of these paintings in my studio, and a publisher, Alain Serres, suggested using them to illustrate a cook-book.

What impact do you hope your art will have on viewers or society?

I hope that my work can make people happy and inspire them to create, as it did for me when I discovered and continue to discover certain painters and artists. That would be wonderful! As for having an impact on society, that seems illusory to me.

What do you want people to take away from your art?

Inventiveness, humour, the pleasure of discovery, and a certain sensuality.

How do you balance art as self-expression with art as a product?

I don’t see art as a product. Of course, I am happy to be able to sell my works to make a living, but I don’t think about that when I create a painting, drawing, or sculpture.

What motivates you and makes you creative as an artist?

It gives me a reason to live and not constantly think about my mortality. It’s my oxygen and nourishment; it keeps me moving forward in life and often allows me to connect with others despite being very solitary.