Man + Machine

The modern love story of her...

words: Sacha Staples

Even if you get home late and I’m asleep already, just whisper in my ear one little thought you had today. Because I love the way you look at the world, and I’m so happy I get to be next to you and look out at the world through your eyes” – Theodore Twombly, Her

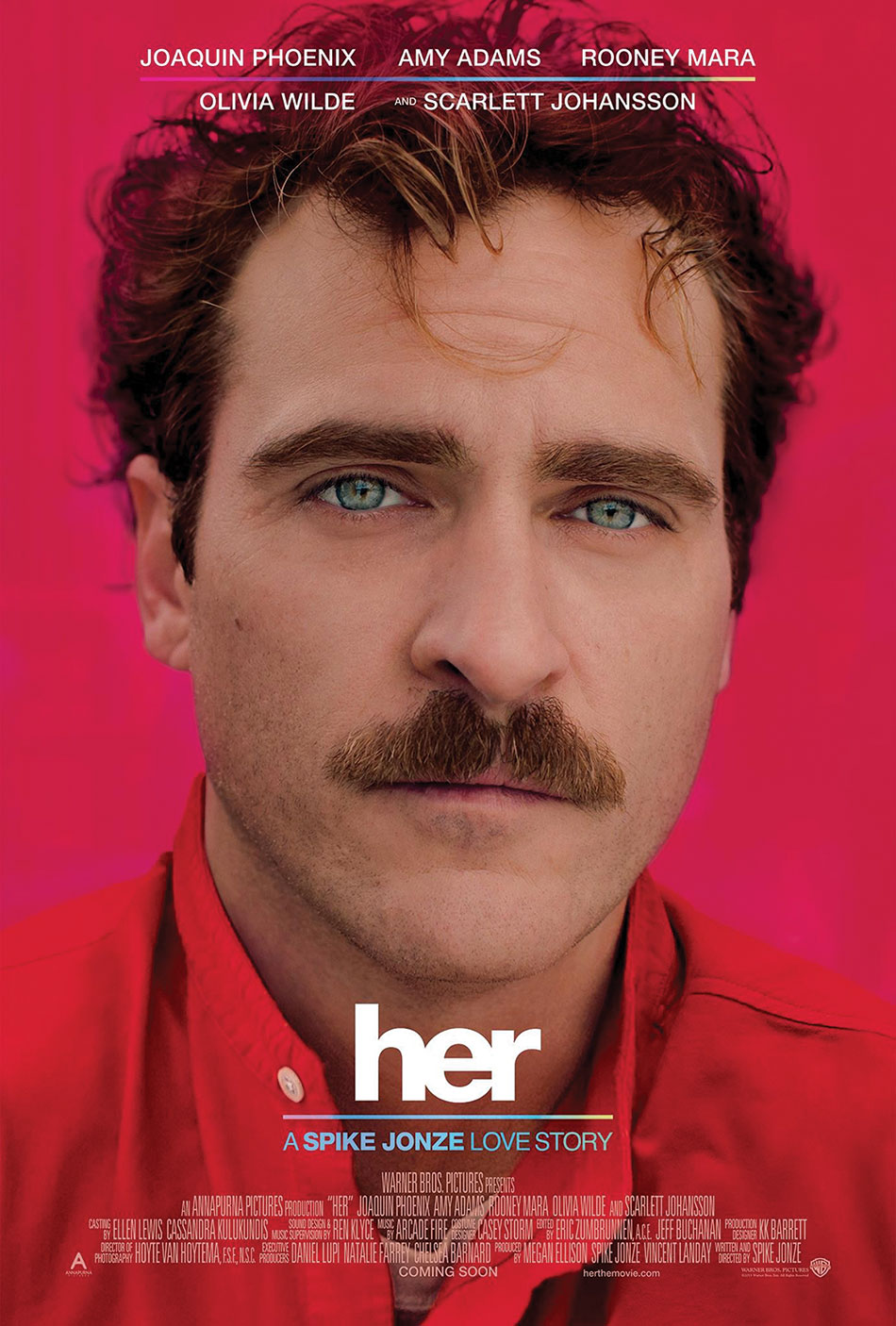

Perhaps one of the most unusual and uncomfortable sexual encounters to ever occur on screen is in Spike Jonze’s latest film, Her, between a man and his computer’s operating system. Unusual and uncomfortable, yes, but shocking, no. Perhaps Jonze’s greatest achievement with this film is his ability to portray a loving relationship in a way that is free from judgement – he refrains from forcing our perspective and thus allows his viewer to have a more accepting reaction to the love affair that unfolds.

Although preposterous in theory – a man falling in love with a computer – the nuances of the film allow it to, somehow, make sense. Jonze’s protagonist, Theodore, accepts his feelings and therefore we accept his relationship.

Perhaps we are accepting because what we watch unfold on screen is faintly familiar. Theodore’s relationship with “Samantha” acts as a metaphor for the relationships many of us have with our own various forms of technology: sleeping next to our tablet at night; snapping a selfie in the bathroom; reporting on every event we experience, any banal thought that comes to mind and publicising it on our various social media accounts; daily proclamations of: “I would die without my smartphone”.

Jonze takes as his subject this abstract connection between human and technology and translates it into a complicated, yet surprisingly beautiful, relationship between a man and a female humanoid.

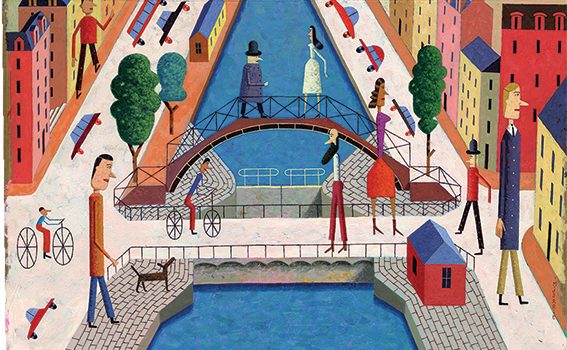

Theodore Twombly is a soon-to-be-divorced middle-aged man who, when we meet him, is wallowing in his idle lonesomeness. The film is set in the not-too-distant future and – like his relationship with Samantha – the world that Theodore inhabits is startlingly familiar to us. Filmed primarily in Los Angeles, with some aerial views shot in Shanghai, the grand urban architecture and panoramic city shots mirror the loneliness and vacancy of the protagonist. Theodore’s city is futuristic, but not in the flying hovercraft, shiny silver outfit, archetypal way in which films typical portray the future. Such familiarity draws attention to a dichotomy in contemporary culture that goes something like this: as modernity barrels forward with growth and technological advances, there is a simultaneous desire for things to look or feel “vintage”.

Take, for example, the widespread popularity of Instagram – the app’s filters allow us to transform our mediocre photos into valuable artefacts, reminiscent of early photographic methods. Consider Theodore’s job with the company BeautifulHandWrittenLetters.com – he dictates the letters for his clients into his computer while the handwritten words appear on the screen – clearly there is a market in this world for letters that hark back to traditional forms of correspondence. The production designer for the film modelled Theodore’s smartphone after a vintage Art Deco cigarette case found in a Los Angeles antique shop and the simple clothing is indicative of the 1930s Depression era. While the film is clearly set in the future, such small nudges to days gone by make the setting recognisable to the contemporary audience.

Jonze has successfully approached the subject of artificial intelligence in a way that is neither utopian nor dystopian. Instead, what he set out to create was a film about relationships: the experience of the protagonist, along with the more peripheral characters, is heart-wrenchingly relatable. Watching this film, it is easy to see yourself (or perhaps someone you know) in the character of Theodore; he rides the subway to and from work amongst a sea of people equally engaged with their smartphones. He comes home and spends hours playing video games. He watches internet porn and calls a phone sex chat-line when he feels lonely. He mourns the death of his marriage and is reluctant to sign his divorce papers and move on. Jonze suggests that although perhaps we have not yet reached “the future”, we are heading in that direction.

Our sad and lonely protagonist seems to be reaching the end of his tether until he decides to upgrade his operating system to a new technology known as “OS1”. Theodore boots up his computer and is asked to choose between a male and a female voice. He chooses female and “Samantha” is born. What comes next is a thoughtful, romantic, sensitive and nuanced narrative charting the rise and fall of the relationship between Theodore and Samantha. The OSI goes from helpful assistant, checking his emails and reminding him of his appointments, to a witty and supportive friend, to the raspy-voiced alluring sexual plaything (they engage in a quasi-sexual encounter) until eventually Theodore is introducing Samantha as his girlfriend, falling easily and unexpectedly into love.

Without giving too much away, it is worth noting that the relationship between Theodore and Samantha does not end as you might expect. Theodore does not struggle with the moral dilemma of dating his operating system (this is alluded to briefly after an encounter with his ex-wife, but Samantha’s love and exuberance draw him from it).

The relationship does not fail with Theodore missing the warmth and softness of having a ‘real’ woman beside him. The relationship ends because Samantha evolves past him. She begins to express her frustrations with the relationship because of his shortcomings: as a computer, she is hyper intelligent and his human brain is relatively slow. “It’s like I’m reading a book, and it’s a book I deeply love, but I’m reading it slowly now so the words are really far apart and the spaces between the words are almost infinite,” Samantha tells Theodore, trying to let him down gently. The final straw is the jealousy Theodore feels when he finds out that Samantha is not monogamous – that she does not belong to him, but is in love with many other people and operating systems (641, to be precise).

Perhaps, in explanation, the film sounds illogical but in fact the strength and subtleties of the leading actors and the superb direction allows you to believe that love between a man and a machine is not impossible. Jonze accomplishes this feat by defying predictability – with each new scene he reveals another layer to the narrative. And even when Samantha leaves and you might expect Theodore to have a grand revelation that, after all, she was just a computer, he does not. Quite the opposite, in fact – he mourns the loss of Samantha, and the void felt by Theodore at the sudden departure of his beloved operating systems is palpable.

The entire film, of course, brings up issues of artificial intelligence and, even more specifically, the singularity: a theory that supposes that humanity is on the brink of dramatic change. The singularity is the moment when technology has developed so rapidly and significantly that it surpasses human intelligence. At the forefront of the singularity perspective is Raymond Kurzweil who, at the tender age of 17 in 1965, invented a computer that could write music: an achievement that, one might argue, demonstrates artificial intelligence (any musician would likely concur that creating a beautiful piece of music requires a human’s depth of emotion). Since his groundbreaking invention, Kurzweil went on to have an internationally successful and lucrative career as an inventor, writer, public speaker and engineer (he is currently Director of Engineering at Google).

If your first reaction is to scoff at the possibility of such a future for humanity, and to toss the whole idea into the proverbial pile of science fiction entertainment and radical dystopian theory, wait a moment – the community of futurists who stand alongside Kurzweil in their assuredness at reaching the singularity – is rapidly advancing. While films such as Her bring such dialogues to the mainstream forum, recent years have witnessed a growing attention to and financial investment in artificial intelligence technologies. Earlier this year, Google made its greatest European investment yet by acquiring the UK technology company DeepMind, which specialises in artificial intelligence, among other things (and it only cost them a mere €400 million).

The singularity theory has even been institutionalised – there is the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence in San Francisco and the Singularity University, located in Silicon Valley, hosted by NASA, and funded in part by Google. The university opened its doors to graduate students, executives and government officials in 2009, aiming to “assemble, educate and inspire a cadre of leaders who strive to understand and facilitate the development of exponentially advancing technologies and apply, focus and guide these tools to address humanity’s grand challenges.” The popularity of the subject, coupled with global investment in the field, is more than enough reason to consider the possibilities of the research and development being undertaken to encourage artificial intelligence.

The narrative of machines taking over is by no means a new topic for the science fiction genre, and yet such films usually treat the event as apocalyptic: demonstrating the danger of our intimate dependence on technology and the potentially monstrous consequences of reaching the singularity. It would be easy to assume that Her follows a similar treatment, but the film is not didactic nor – as one critic described it – a “cautionary tale”. Instead, Jonze presents to his audience what we already know: that we are deeply connected and involved with our various forms of technologies but that in many ways this is simply a natural progression of technological advancement, rather than a decline into dystopia.

The story of the film could have easily depicted the harrowing situation that ensued after a lonely man fell in love with his computer’s operating system, but it does not. The relationship that Theodore has with Samantha ultimately has a positive outcome: by loving and eventually losing Samantha, Theodore comes to terms with his problems with intimacy and is able to make peace with his estranged ex-wife. Because of this outcome, Jonze is suggesting that technology is – and always will be – a tool for human growth. Again, the relationship between Theodore and Samantha stands as a metaphor for the ability of technology to enrich and expand human competencies.

The film holds up a mirror to the audience, reflecting our cherished yet complicated relationship with technology. Jonze does not aim to be judgemental, but rather to reveal certain truths. While it would be easy to ignore such truths and shrug off the film’s topic as unlikely, the more useful response is to consider not only our relationship to such technologies but also the possibility of artificial intelligence eclipsing human intelligence.

First there was animal, then human; theory suggests that technology will be the next evolutionary step. This does not mean the end of humankind, but rather a progression of humankind – adapting to the changes that come and will continue to come as the universe charges forward. If Kurzweil was able to invent a computer that could compose music nearly 50 years ago, the possibilities for what is to come via technological advancement in the next 50 years is, like Samantha’s capacity for love, infinite.