My reality – old masters new meanings.

A profile on award-winning Zimbabwean artist Richard Mudariki

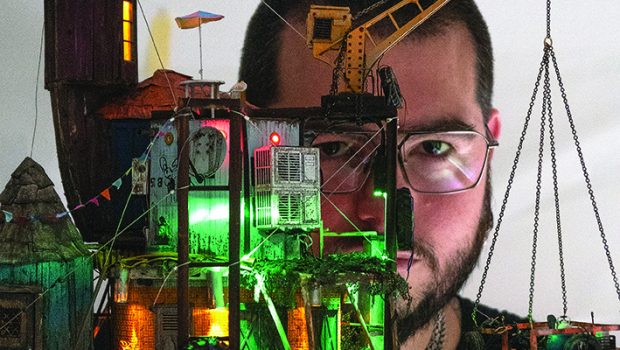

Richard Mudariki is an award-winning Zimbabwean artist who has already exhibited widely in Harare, Cape Town and Johannesburg. Vamp tracked him down in South Africa in time to share his latest achievement, taking part in this year’s 6th FNB Joburg Art Fair (sponsored by first national bank) with three paintings forming part of the ‘In The Shadow of a Rainbow Group’ exhibition curated by his Gallerist, Johans Borman Fine Art. We find out more about the man behind the paintings from his latest collection presented at his first solo show.

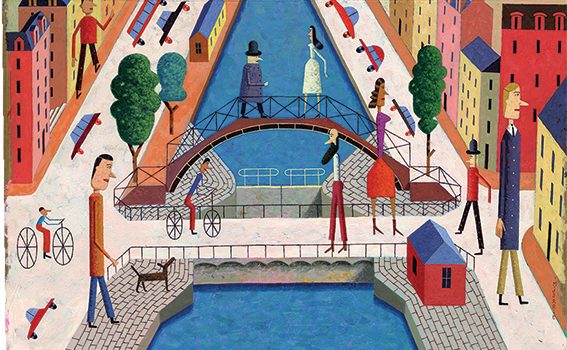

Mudariki has been living in South Africa for the past year, and My Reality, his first solo exhibition, presented a body of work that reflected the ongoing crisis in Africa. However, despite the exhibition title, his paintings make no pretence at portraying real events. Mudariki candidly admits” that they are fabrications taken from the work of Old Masters, but the figures portrayed are taken from their original historical setting and brought into a contemporary world where some place Zimbabwean President Mugabe’s dictatorship at centre stage and others draw attention to other injustices from further afield.

Mudariki’s work can be compared to that of Johannes Phokela, a South African artist of an older generation, who has made his mark both nationally and internationally. Phokela may well have come to Mudariki’s attention and influenced his oeuvre, as both artists rely on appropriation. The South African pillages the canon of the great Dutch and Flemish Old Masters of yore, such as Rubens, Brueghel and Jordaens. However, instead of using Western painting to cast light on contemporary Africa and its problems as does Mudariki, Phokela changes the race of the original 17th-century Dutchfigures from white to black in order to challenge the European myth of white supremacy, and to condemn the racism and colonialism to which it gave rise.

Mudariki’s art is issue-driven: it addresses the violation of both human and animal rights, corporate greed, gender stereotyping, censorship and rape inter alia. Although such subject matter can come across as shocking, the specific political message becomes subsumed in a spectacular Breughelesque pageant of infamy and transgression.

This transcends any chronological and geographic particularity, and becomes a timeless and universal statement conveyed with such gripping imaginative assurance that the resultant image entirely transcends the artist’s activist goals. Mudariki takes canonical masterpieces of the order of Goya’s Third of May, Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa and Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass – works of such devastating impact that they have etched themselves indelibly in the memory of many successive generations – and he appropriates them without ever reproducing them.

“Mudariki’s art is issue-driven: it addresses the violation of both human and animal rights, corporate greed, gender stereotyping, censorship and rape inter alia.”

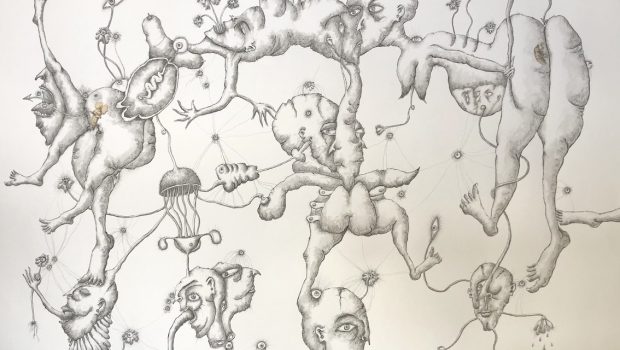

Although he retains the compositional formulae and poses, the physiognomies, anatomies, costume and other details are always totally changed to shatter the illusion of reality, disorientate the viewer and make him question what he is looking at. Mudariki’s most startling transformation of these revered museum pieces is the way he transplants his ‘borrowings’ into jarring settings that are completely alien to the backgrounds of the original paintings. Thus Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa no longer sails the high seas, but is decisively planted on terra firma with the smashed raft being equipped with humble box-cart wheels.

This creates a deflationary effect of parody and burlesque, and there is indeed an element of send-up in many of Mudariki’s paintings. Gericault’s figures materialise on a corridor-like stage where they are penned in by claustrophobic, inward-pressing walls that steep the scene in menace. These stark, bare and emptied-out spaces, devoid of windows, doors or any other kind of opening, appear to form part of a dark labyrinth of sinister Kafkaesque design. Mysterious maze-like structures and slabbed, cubic boxes occur throughout this body of work, injecting a surreal complication into imagery that was originally constructed in a purely naturalist manner, reproducing the viewer’s own familiar world.

Ominous overtones go hand-in-hand with humour: the sight of Helen Zille leading her forces into battle is extremely amusing. So is the idea of placing Manet’s two bachelors picnicking with a naked woman within a stadium or cyclorama where there is no vestige of privacy.

Mudariki’s comic sense often verges on the kind of black or gallows humour that we associate with the theatre of the absurd. Extremely obtrusive checkerboard patterns invade the walls and floors of Mudariki’s walled spaces, turning them into three-dimensional chess boards. Chess is an ancient game in which the two players enact mediaeval battles using stylised miniature kings, queens, knights and bishops, armies of pawns, and strongholds in the form of ‘parapetted’ castles.

“Ominous overtones go hand in hand with humour: the sight of helen zille leading her forces into battle is extremely amusing”.

Checkerboards are also associated with other games of skill and chance, such as checkers and draughts, which also involve combat, the capture of pieces and the conquest of territory. These allusions suggest that the paintings represent contests, and they identify life as conflict and strife. Both the checkerboard upon which the action of virtually all the paintings is set, and the walls cordoning off space – thus denying one any glimpse of what lies beyond – imply captivity and confinement, and act as metaphors for people denied freedom of choice and room in which to manoeuvre. All these walls, barriers and boundaries imply no exit, and distil a hallucinatory quality indicative of dementia and delusion. Mudariki’s set-ups function as visual parallels to Zimbabwe, and all tyrannies, where a reign of terror prevails and life is a dicey and uncertain matter of continual jeopardy and risk. Under such pressure, a person’s mental state can deteriorate into one of fear, apprehension and,eventually, paranoia.

Mudariki’s isometric boxes function exactly like a stage with the fourth wall removed, and the artist’s décor exudes an overt theatricality, conjuring up a chimerical world that is both grotesque and macabre. The bizarre architecture, freakish hybrid beings and flamboyant costumes are scenographic fantasies. They remind us of the mediaeval visions of Brueghel and Bosch, both of whom rejected the real world in order to construct an infernal amusement park, a Disneyland of the afterlife – in the words of W.S. Gibson. The masks and costumes of different eras and different societies smack of disguise, travesty and duplicity, and proclaim that appearances are deceptive, and nothing is what it seems.

Mudariki’s debts to other artists are almost exclusively limited to quotation. The suited militarists, businessmen and politicians often vaguely remind one of those of the German Expressionists. The forced perspectives and love of dusky blues and greens owe something to Giorgio de Chirico, and the animal-headed beings, recall the half-animal, half-human creatures of Alberto Savinio and, of course, Brueghel and Bosch. Many of the paintings create a surreal atmosphere, yet do not suggest the influence of any one particular painter. These are indeed lean pickings.

No artist emerges from a void, and one is forced to ask oneself what tradition it was that produced Mudariki. The answer is that the artist takes the paintings of the Old Masters and transforms them into allegories. This makes him something of an odd man out, as this mode of communication became increasingly spurned over the last century because it reeks of the Symbolist movement, and the outmoded art of the turn of the 19th century.