Pentedatillo

Richard England reminisces about Pentedattilo with its poetic setting and sinister tales

Sometime ago, I received an invitation from the University of Reggio Calabria to act as one of the tutors in a workshop to be held in the nearby abandoned village of Pentedattilo. Not knowing of Pentedattilo, I must admit that my initial reaction was to decline.

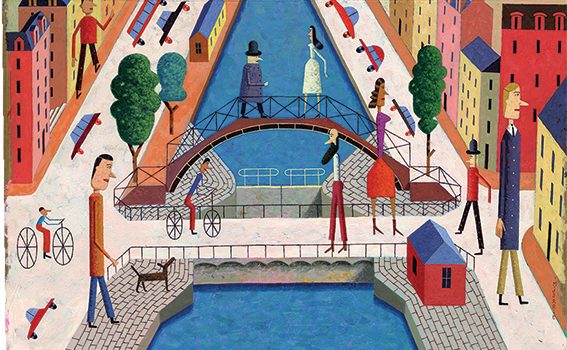

Curiosity, however, led me to investigate and my searches soon led me to discover Pentedattilo renderings by Edward Lear and M.C. Escher, both of who had produced drawings and paintings of Malta. This solicited further research, which revealed both the suburb’s exotic setting and also its sinister background and history. What enticed me to finally accept was Sestito’s choice of tutors; a group of multi-disciplinarian artists and architects whose presence promised interesting and intellectual interchanges.

As the place, its history, its fairy-tale setting and the choice of fellow tutors lured me to acceptance, I arrived in the dying hours of a hot summer day with the ruins of the abandoned village illuminated by the vestal rays of a setting sun. The place immediately emanated a sense of magic; yet still, it seemed to be overtaken by a strange, catatonic atmosphere.

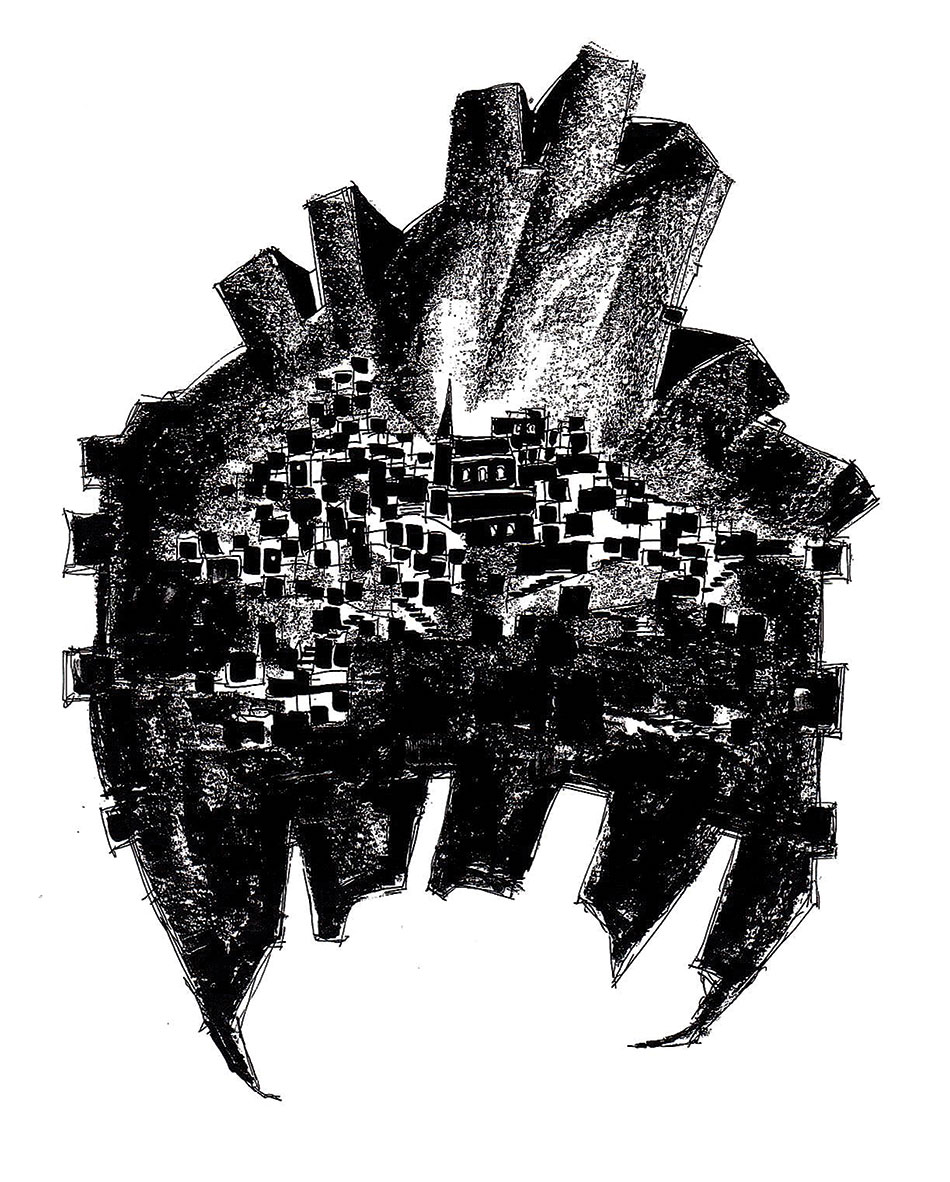

My seven-day stay in this chimerical ambience, working with one of the most enthusiastic group of students I have ever encountered and enjoying enlightened intellectual exchanges with the other tutors, has left me to this day with lasting memories and a special affection for the place. Nestled in the hills of the Ionian Aspromonte at the toe of Italy, under the dominant five fingers of the mountain’s giant hand, Pentedattilo lies 30 kilometers from the town of Reggio at an altitude of 450 meters.

Marcello Sestito, in his book ‘Pentedattilo – Palmo di Pietra’, makes a specific reference to its paradoxical position, referring to it as “the hand in the foot”. Its houses and two churches form part of an ancient Greek area of Calabria, where, to this day, traditions still reflect their origin. Deriving its name from the Greek words ‘Pente + daktilos’ meaning five fingers, the place manifests a combination of exceptional natural formations with a particular architecture at a time when man was still concordant with nature, and used its materials diligently while also listening to its voices.

The abandonment of Pentedattilo was due to devastation by floods and earthquakes, attacks by pirates and the catastrophic damage caused by the tremors of 1783 and 1908. By the middle of the last century, at the end of the 60s, the place was already almost completely uninhabited with most of the young generation having left in search of more lucrative lifestyles. Little wonder that the locals now refer to the place as “Il Paese Fantasma” (The Ghost Village).

“The traveller finds again a past of his that he did not know he had; the foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in these foreign unpossessed places”

Today, from its ruined houses, prickly pears, citrus fruits, olives, mimosa, almonds and other Mediterranean flora flourish within the walls of the original dwellings. It is as if the ruins are now adorned with the growth of nature. Gustave Flaubert expressed the penchant for the combination of nature and ruins when he wrote “I love above all the sight of vegetation resting upon old ruins. This embrace of nature coming swiftly to bury the work of man”.

In this hillside cluster, the spirit of place is truly meaningful and the stillness, silence and hidden memories of the place combine to create an esoteric atmosphere. It is as if ruins and nature combine to give the place a sense of numinous sacrality. Rose Macaulay, the English novelist, in her ‘Pleasure of ruins’ points to this “strange human reaction to decay”. Perhaps it is because each of us restores ruins back to their pristine state in an entirely personal manner. Remains and fragments seem to appeal more to the spirit than the eye.

The truth is that fragmentation remains more appealing than wholeness. In the presence of ruins, as receptacles of memory, the tendency is for one to meditate and mourn, while rhapsodising across the rivers of time. Little wonder that great artists such as Piranesi, Salvator Rosa, Poussin, Panini, Lear, Escher and others were haunted by the misty miasma of decay. John Piper, who painted many of England’s ruins, wrote “there is one odd thing about painters who like drawing architecture, they hardly ever like drawing the architecture of their own time and prefer the ruins of the past”.

There is little doubt that every ruin holds within it a story and also that buildings in ruins somehow appear more beautiful than when they were intact. Edgar Alan Poe reminds us that the stones of ruins, not only possess a mysterious potency, but are also pregnant with an inherent magical quality.

“We are not desolate we placid stones

not all our power is gone …

not all the magic …

not all the wonder …

not all the mysteries that in us lie”

It is as if each particle of a ruin holds within it the mnemonic stratified layering of all the stories of its past. Even before its decline, Pentedattilo held a fascination due to its evocative setting. Its earliest rendering comes from the hand of the 17th century polymath Athanasius Kircher who after travels to Malta and Sicily depicted Pentedattilo in his 1678 ‘Mundus Subterraneus’ with a supplementary drawing of a foot at the bottom of the page, as if again to hint at the paradoxical “hand in the foot” location.

The ruins of Pentedattilo are, however, not only the ruins of history but also narrators of the ruins of lives. On the Easter Sunday of 1886, the place witnessed a brutal massacre in the Alberti Castle situated at a 360 degree vantage point between two of the towering five fingers of Monte Calvario. The Albertis, owners of the Pentedattilo territory, had long battled on territorial and boundary matters with the Abenevoli family. Bernardino Abenevoli, son of the Baron of Montebello, desired Antonietta Alberti in marriage. However, because of the family feud and her engagement to the son of the Viceroy of Naples, his proposal was defiantly denied by her family. Bernardino, furious at the rejection, sought sinister revenge. On the night of the 16th of April 1686, having been let into the “three hundred door castle” by a disloyal member of the Alberti staff, accompanied by a group of assassins, he carried out an outrageous massacre, killing most of the Alberti family and abducting Antonietta and forcing her into marriage. Legend recounts that in the agony of his death, Antonietta’s brother, the Marquis Lorenzo Alberti reached out and planted the effigy of his blood-stained hand on one of the castle walls; an imprint of the morphological profile of the castle’s background silhouette. Bernardino’s union with Antonietta obviously did not last. Now a fugitive, he was forced to escape, initially to Malta and subsequently to Vienna, where he was killed in battle. Antonietta, despondent and forlorn, spent the rest of her life in a convent in Reggio Calabria.

…”Human blood spilt in anger and revenge seems to leave an indelible mark on the locus where the event occurred.”…

Walking the winding streets of this ruined place, one can almost sense, in the echoes of its veins, the somnambulant ghosts of the Alberti family lurking tenebrously, in their maledictions of martyrdom. With each step taken on these time-worn tortuous pathways, one can imagine hearing the footsteps of the dead. In such an ambience, not only the ears listen, but also the eyes. The empty house-shells in the proximity of the castle ruins echo spectral haunting sounds of voices of anguish and suffering. It is a truism that a place absorbs its experiences, as it is also true that the flow of human blood disturbs a place forever. Human blood spilt in anger and revenge seems to leave an indelible mark on the locus where the event occurred. Time may shed memories but place retains, recalls and re-echoes events which become an inherent chapter of the site’s mnemonic narrative. In the tarnished and embalmed mantles of this place, as I roamed the cavities of these amnesiac dwellings, close to the exiguous ruins of the castle, I sensed only odium. Tracing one’s way through the skeletal carcasses of the buildings, tinted salmon and rose under the light of a waning moon, spectral voices traverse the bridge of the great divide, echoing their lament across space and time. In the canyons of this graveyard, the sounds of the past seem to meander through the corridors of time in shadowed whispers to claw at one’s innermost feelings.

Continuing the arduous climb, past the church of St Peter and St Paul, revealed the remnants of the castle. Here, the fecundity and power of nature have overpowered the hand of man as if to obliterate the memory of that fateful night. The castle has now decomposed to nothingness, yet still its few remains brood dark and sinister, as in a vain attempt to hide its lecherous past. Little is left of this once dominant splendid abode; yet its absence reflects a potent presence. It is as if its now miniscule relics chant a sorrowful requiem. In this place, a futile search of longing fills the air. Voices are heard, voices from the earth, yet, not of the earth, voices of in-between, voices of ghosts who perhaps still roam the castle tomb, hovering in ever-restless sleep.

Pentedattilo, once of the living, now but a death mask, is a mirror of its own past in timeless suspension; its narrative, scripted in latitudes of longing and longitudes of loss. Today it is an architectural spectre petrified in soporific trance chanting antiphons of sorrow; a limbo of emptiness and desolation. Each step taken and each corner turned is laden with memories. Despite its silence, Pentedattilo shines as a pulsating portrait whose saddened song-lines echo against its five-fingered “mano sinistra” (left hand) mountain canvas. Its tenebrous history reaches over the arcades of time in enigmatic De Chirico silences, evoking unrequited mnemonic remembrances. As time moves forward one will soon never know what it was like to live here. As years lengthen and vegetation continues to grow, these ruined stones will lapse into silence, yet, they will still, in future, recount the sombre narrative of the place.

I left Pentedattilo drunk with its eeriness, silence and beauty. To this day, it still haunts the chambers of my mind and beckons me back to track once more its lonesome paths and hear its wounded songs. Its stones have known death and in the process have lost desire. It remains a locus where prose is perhaps incapable of expressing its true essence and real spirit.