The enchanted isle

Richard England on his Aegean cruise after a long and demanding work period

BY RICHARD ENGLAND

My wife’s objective was for me to nurture a period of relaxation to find time to allow my soul to catch up with my body. Not being inclined to either relaxing and less so to cruise trips, the sole reason for my consenting was that the itinerary included stops at Ephesus and Santorini, locations I had long desired to visit. As the boat left Piraeus things already seemed not to augur well. The sea was rough and a strong meltémi was blowing; an ill omen for one not being too good a sailor. Soon a full scale storm was brewing and a decision was taken to drop anchor at Mykonos for two nights, curtailing the scheduled itinerary. When the boat eventually set sail, it was announced that the visit to Santorini was to be reduced to a mere couple of hours. Despite frustration and a not yet full recovery from sea sickness, the sight of the island as the boat approached, provided an eye-caressing and knee weakening experience, if no remedy for my discomfort. Rising from cobalt waters, the lava cliff-face, capped by the super-imposed skyline of albescent buildings presented a visual symphony so ethereal and magical that it seemed to belong to the realm of myths. Nietzsche was right when he wrote “Architecture is a sort of oratory of power by means of form”.

As the sounds of a dying wind and the lapping waves of the now less turbulent waters merged into a hushed chorus, I gazed in awe at the man-made mantle of undulating whiteness; carving diaphanous thresholds between earth and sky, while recalling that the etymological root of the word ‘white’ is the Germanic ‘blank’ meaning ‘brilliant’.

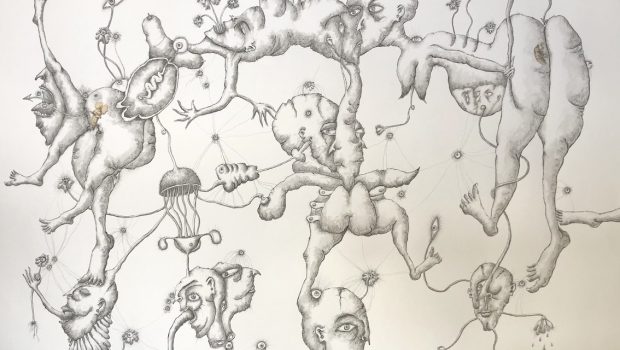

On landing, the all too brief time, spent mostly wading one’s way though tourist crowds, was however sufficient to whet my appetite for future extended visits. This initial contact, despite brevity and chaos still proved to be spell-casting. The island lured me to return, inviting me to draw, what Greece’s Nobel Prize poet Odysseas Elytis referred to as its “lamp black quality”, “drinkable blue volcanoes” and “Medusa-like domes”, together with the melodious orchestras of its ivory buildings perilously perched on the ravaged and agitated topographies of an island born “out of the bowels of thunder”. From that moment, I yearned to roam its snaking streets to discover and delineate the hidden secrets of this miniscule land, defined by Greek architect Alexander Tombazis as “built form poetry of sublime beauty”. Long ago, I had understood that what you draw remains with you. You absorb the whole, eliminate the non-essential, then render the essence and spirit of place, for as Paul Klee correctly stated “the art of drawing is the art of omission”. In that all too short a visit, an urgent need arose within me to explore, draw and retain in memory the sun-baked dancing collages of this maze-like labyrinthine entity. It was Basil Spence who once told me that “to draw a place is to savour its unknown reality”.

Back on the boat, still intoxicated by what I had sampled, if frustrated by what I had missed, I pondered on the island’s beauty, and a decision to return was soon taken …though not in the tourist season. In an hour of enticement, this volcanic island topped by its man-made Malevitch geometries had spun its spell …the ebony siren of the Aegean Sea had sung its seductive song. In those fleeting moments, I knew I could never escape it, for like George Seferis, I understood that “this place would keep wounding me”.

Three years later I return to the island, this time for an extended visit, armed with pens, oil pastels and drawing pads. It is winter and the sea is sulphur-tinged; the caldera diabolical and plangent, and the island silent, veiled in a muted stillness. Tourist haunts are closed and shuttered …and an eerie absence prevails. The black cliff-face and the now amber string of cubist geometries have descended into a wintry dreamless sleep. Like a chrysalis, the town is seemingly inert, as if attempting to obliterate the lurid memories of the chaotic turmoil of its rampageous tourist months. Now it is in an anaesthetic trance, impregnated with quiescence; not unlike a city of the dead …but still a remarkable spectacle.

At eventide, as the sun sets in a prism of colours, the clouds dance jazz-like music on the canvas of the sky. Night sets in and an uneasy lull descends. All is enchanting …crying out to be captured. I draw well into the night, for the island’s built-forms, clothed in lambent moon-light, are now even more mysterious. It is good to feel that eye and hand are still in unison; the hand acting as a sensitive seismographic marker, etching on paper the tremulous registrations of the eye. Walking the church square in Oia is not unlike way-finding oneself through a Giorgio De Chirico canvas with its metaphysical overlays of “lengthened shadows” and “mathematical enigmas”. As the moon casts secret shadows on the old walls, the rustle of a strange music prevails. The mood turns malevolent, the sea below is mercury tinged and the white walls pale to opaque grey mirror panes. Nocturnal shadows manipulate the laws of perspective and I, linger as in a timeless realm, attempting to trace what is fast becoming a lugubrious narrative. The austerity of this spectacle, reminds me why this land was once considered the favoured home of vampires.

The next morning, the mood changes, the sun shines, all is incandescent and the sea is once again a rapturous Klein blue. A resplendent violet aura transforms buildings into alabaster sculptures, “playing and changing shape every moment in shadow and light” (Nicos Kazantzakis). At noon, a Taverna in one of the winding alley-ways of the town, crowded with black-clad figures playing backgammon, offers solace, shelter and nourishment in the form of dolmadakia washed down by perhaps too many a glass of mercuric retsina. In return for the hospitality offered, I leave one of my drawings with the owner, perhaps to mark in time my passage there.

This is the island which once taught Le Corbusier to appreciate geometry. Here shadows speed over surfaces to mark the passage of time; each wall and dome a time-keeping gnomon. Escher-like stairs and planes proliferate, beckoning one to discover further straggling forms cascading down zigzag levels of precipitous cliff-faces. Even though the wind’s murmur still haunts the canyon streets, all is sun-drunk and for an instant I imagine I am in Italo Calvino’s city of Zora “where patterns follow one another as in a musical score” and “where not a note can be altered or displaced”. Harmony reigns in these structures which seem, in the words of Aris Konstantinidis as if “they were made not by human hands, but by gods”.

“The greek islands are a constant art lesson… the rarest of sculptural atmospheres”.

On Santorini, architecture is the result of human intelligence responding to basic needs. On this volcanic rock, topography and architecture merge into a metamorphosed part troglodyte-part built amalgam and alloy described by Bernard Rudofsky as “one of the strangest places this side of heaven”. Anonymous craftsmen were constantly creating sustainable solutions in a struggle to provide shelter in a not too hospitable environment. This “architecture without architects” reflects the perfect universal ethos of shelter construction in relation to available conditions.

Though nature, through its devastation caused considerable damage to this island, it was the change in the meaning of the sea which inflicted the most spoliation. Originally a pirate-carrier, the waters around the island now serve as a tourist vehicle and the consequential pressures of speculative development are all too evident. A once dreamlike utopia is rapidly being transformed into a money-making machine dystopia and as with all Mediterranean coastlines, tourism and greed are fast destroying the ethnic character of this exiguous land form. Yet, despite the rampant tourist trade, in the winter months, the island still much of its original artisanal ambiance and age-old traditions.

On a return journey from the still smoldering volcanic isle of Palaia Kameni, I am again fascinated by the skyline of the dancing geometry linking Imerovigli, Firostefani, Oia and Fira and I recall that it was here, according to legend, that the lost city of Atlantis once thrived.

As if still mourning its loss, the 400m deep sea is dark and cheerless. Once again on the main island, visits to some of the smaller villages, offer more succulent material to render. Miniscule Megalohori provides a picturesque townscape, while the defiantly perched Imerovigli and the adjacent rock-embedded Theoskepasti Chapel stand out as particularly stunning gems. Everywhere geometry prevails as if echoing Cezanne’s words that “everything is formed according to the sphere, the cone and the cylinder”. Later as I visit Emborio, I recall that Sartre had used this village as the setting for his play Les Mouches.

Time is running short. Laden with over one hundred drawings and a heavy heart, my visit comes to an end. Parting is not easy for the island (in Greek mythology a gift to the Argonauts from the sea god son of Neptune and Venus) again lures me back. There is, I know, more to see and draw. Travelling in such an ambiance is an enlightenment and education, and drawing remains the ideal investigational tool. Akrotiri, the “Pompeii of the Aegean” summons, the legend of Atlantis beckons and the mandatory 300m, 500 step, zigzagged donkey ride from Athinos to Fira remains a tempting, if daunting adventure. All, however, must wait for a future visit, for Santorini, like a sanctuary religiously beckoning its pilgrims to return to its shrines, calls me back.

After a decade, still impregnated with haunting mnemonic images, I return, armed once more with drawing materials and camera carefully dispensed. The ten year passage has been tinged with what Milan Kundera termed “a suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return”. The rejection of the camera stems from my predilection to establish direct links between what my eyes see and what my hand draws. It was Le Corbusier himself who dismissed photography as “a tool for the idlers who use a machine to do their seeing for them”, for the camera looks at the subject as opposed to seeing it. The object remains that of capturing the passion of the place and its genius loci. I have always believed that drawing sweetens the road travelled.

As our planet today rapidly dissolves into a characterless global village, situational and unique environments, such as those of Santorini, offer man much needed soul enriching antidotes. It is the authenticity of these ambiances that we must today strive to preserve.

If Santorini does not posses the one single edifice to match the plasticity of the Paraportiani Church on Mykonos, the Panagias Chozoviotissas cliff-hanging Monastery of Amorgos, or the delectable dovecotes of the holy island of Tinos, it does harbour in its array of blinding white villages, a unique canvas of timeless architecture. On this isle, one comes not only to view architecture, but to fully experience the island’s beauty, for Santorini remains a perfect tableaux of platonic solids counteracted by intriguing in-between spatial voids. Here, place-making balances way-finding, as one experiences a true ‘promenade architecturale’. Santorini remains a miraculous man-made patrimony, a personification of the real values of life, a lyrical locus where, in Nicos Kazantzaki’s words “never have grace and power merged so organically”.

The place continues to entice. This amalgam of Earth, Fire, Water and Air invites future visits, for the Siren of the Aegean Sea remains a tantalizing and alluring temptress.