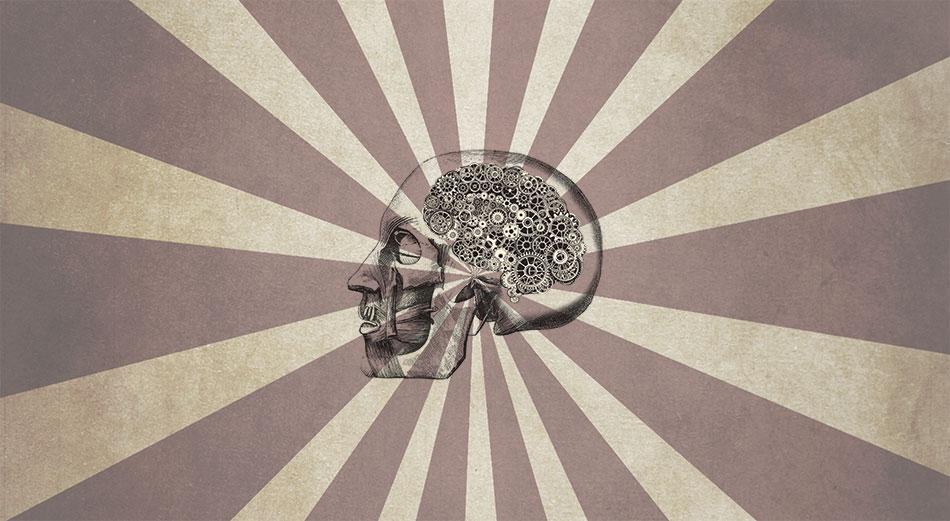

Evolution of our species

Technology has the potential to change every aspect of what we are as human

Words: Kasey Detmar

When I was a kid, there was a small room that held a double bed and a TV in my family home. On Saturdays, all that could be heard throughout the otherwise quiet house was the click-click-clicking coming from that room. It was us on our Nintendo, our little hands with a vice-like grip around those remotes, thumbs furiously controlling the direction panels with natural expertise. Every now and then an adult would pass by and insist on having a go. They spent so long looking from the screen back down to their hands to try to figure out how to control the remotes that they rarely got the chance to play before both their frustration and ours booed them out of the room.

I would hear the adults talk amongst themselves about their amazement at our hand-eye dexterity. “Even the very young ones. It’s incredible.”

Nowadays, give a small child an iPad and they not only understand that touching the screen yields results, but they also comprehend the specific movements to achieve various actions.

It’s hard to remember how we functioned efficiently pre-email. Today you would have to be over 25 years old to have experienced the world without the world wide web.

What effect is this having on the cognitive evolution of our species? Is it making us dumber or smarter? Google allows us to do a wide spectrum of things we could have never done before. The question is, are we learning these skills, or we merely executing what we are reading? Will we retain this information, or simply depend on Google for the next time we need to remember how to approach the task at hand?

Researcher Betsy Sparrow of Columbia University found that people were much less likely to remember particular facts if they believed that the information would be accessible to them in the future. When presented with random facts, participants in a study who believed the information would be lost after they read it scored much higher on the quizzes that asked them to recall the facts than those participants who thought they could access the information later. She also found that most people immediately turn to the Internet when they are presented with a question to which they don’t know the answer. Further to this, she also discovered that people prioritise remembering where certain information can be found over the information itself.

It’s two-sided: while too much use of the Internet can lead to addiction and shorter attention spans, it has also been shown that being Internet-minded gives people the potential to learn even more. However, in order for this to happen, it’s necessary to have educational systems that embrace how young people think today, and cater to their particular needs.

My generation will forget what we learned from Google from one day to the next because we have not been taught how to possess an Internet-orientated way of thinking. Our children on the other hand, are evolving to understand the way in which to think in order to obtain and learn the information in a different way. But then what exactly does this imply?

The Internet has become today’s primary source of memory that uses external sources to store and to retrieve information (transactive memory). As a result, children might not be as detail oriented in their studying. Whereas we used to ask people for details, we now first turn to the Internet, then consult others, so our need to remember details is lessened, since we have a permanent and steady go-to source for our questions. Having said this, the lessened burden of remembering details allows children to form a bigger picture, giving them the capacity to learn so much more, and has the potential to make them smarter on the whole.

“The lessened burden of details allows children to form a bigger picture, giving them the capacity to learn so much more, and has the potential to make them smarter on the whole.”

While Internet-orientated education might prove positive, what could possibly be the effect of the constant stimulation that email and messaging have on a child’s focus and productivity? Children have a relatively short attention span as it is. They typically struggle to manage time wisely and to resist impulsive behaviour. So add the Internet and a constant barrage of communication from their friends to the equation, and it becomes an inevitability that they will be disadvantageously wired differently. Internet addiction is a growing issue in psychiatry because as exciting to the brain as it is, stimulation triggers dopamine releases. As a result, once children get used to this constant dopamine release, they can begin to feel bored without it.

This instant communication can also effect children’s need for instant gratification. Good things come to those who wait no longer applies in our world. No matter how specific, we get the information we need instantly. Regardless of the distance, we communicate immediately. We can order anything we want and it will come directly to us. It will become increasingly more difficult to teach a child the virtue of patience. While patience is all about restraint, it’s also about the state of endurance under difficult circumstances. Children will no longer need to make the choice between a small reward in the short term, or a more valuable reward in the long term. Humans and animals are already inclined to favour short term rewards over long term rewards, despite the often greater benefits associated with long term rewards.

Facebook is only seven years old and children under the age of 13 are not officially allowed to join, so researchers have not had much time to study the emotional, physical, and psychological effects it could have on kids. However, upon his research on the cognitive and psychological affects of Facebook for the American Psychological Association, Psychologist Larry D. Rosen found both positive and negative truths.

Rosen’s first finding was that young adults who have a strong Facebook presence show more signs of psychological disorders, including antisocial behaviours, mania and aggressive tendencies as well as more narcissistic behaviour than those who don’t use Facebook as much.

Rosen also found that the distraction of Facebook can have the obvious negative impact on learning. Studies found that middle school, high school and college students who checked Facebook at least once during a 15-minute study period achieved lower grades.

Rosen said new research has also found positive influences linked to social networking. Some young adults who spend more time on Facebook are better at showing “virtual empathy” to their online friends. Online social networking can help introverted adolescents learn how to socialise behind the safety of a screen. When making friends on Facebook, kids are more likely to overlook race and make friends based on interest. Facebook can also raise self-esteem with happy birthdays, handshakes, likes, and words of encouragement.

Humans are evolving, but which way it will go is still uncertain. Will we evolve into impatient, antisocial and aggressive beings? Or will the Internet learning experience create a smarter, more communicative and empathetic species? Watch this space for a substantial shift in education methods and a whole new level of the social experience.