Dancing architecture

Architecture that embodies the heart and soul of samba...

By Simon Grech GRECH&VINCIARCHITECTURE&DESIGN

It was two in the morning, hot and sweaty, and we were watching tanned, strong, curvaceous dancers contrasting with their pink outfits in the Mangueira Samba School’s practice hall, twisting and turning, committed to their carnival sequence. We were in some part of Rio known to be a little bit dangerous (perigoso as a local – otherwise known as a Carioca – would put it) close to the Maracanã stadium when it came to me that there is a possible direct correlation between the way people dance and the way people build. If one had to say that dance is a mode of communication and therefore a language it would be fair to conclude that the dance of choice for most important Brazilian architects of the 20th and 21st century would be Modernism or Brutalism.

There is a strong tradition of modernism that has been passed from one generation to another and is practised with a certain pride by the young and budding Brazilian architectural practices and architects that feature in popular glossy architectural magazines and websites. Young architects today like Triptyque Architects, Guillaume Torres, and Marcio Kogan – who followed in his father’s footsteps – are bringing it back after death with a certain ownership and flair.

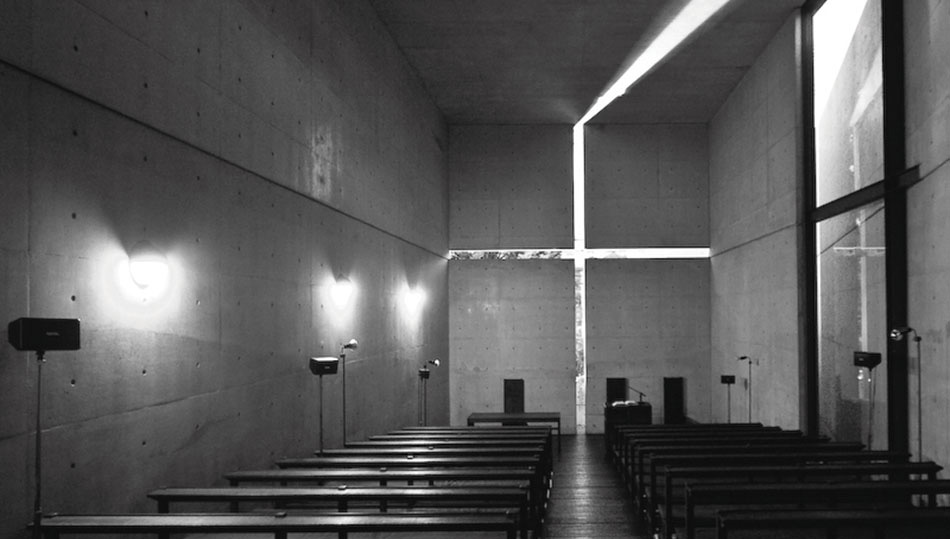

One of my favourite buildings is Paraty House, designed by architect Marcio Kogan of MK27 Studio – who I bumped into, by the way, and who has a most pleasant character. The building is a good example of MK27 that showcases their strong modernist approach, with its long and horizontal elevations stretching over the Brazilian landscape of Paraty. Comparing two different schools of modernism from two different continents would help to further understand the Brazilian ‘style’. For the best comparison, I choose to do this with the Japanese architect Tadao Ando with Oscar Niemyer and Paulo Mendes da Rocha’ .

Tadao Ando’s architecture can be described as being clean, controlled, quiet, calm, precise, perfected, serious, austere and monk-like; Oscar Niemeyer’s as loud, daring, fast, sexy, curvy, humorous and confident and Paulo Mendes Da Rocha’s as raw, rough, brutal, strong and flowing. Similarly, there is a stark contrast between the two traditional dances of these two cultures: Odori for the Japanese and Samba for the Brazilians. Odori is somewhat similar to Ando’s Architecture whilst the architecture of Niemeyer and Mendes embodies the soul of Samba.

…”There is a strong tradition of modernism That has been passe d from one generation to another that is practiced wi th a certain pride by the young and budding brazilian”…

In 2006, Ana Paula Evangelista was named Queen of Carnival and in the same year, Paulo Mendes da Rocha received the Prizker Prize for his contribution of excellence to the architectural world to join Brazil’s architectural champion who won it in 1988.

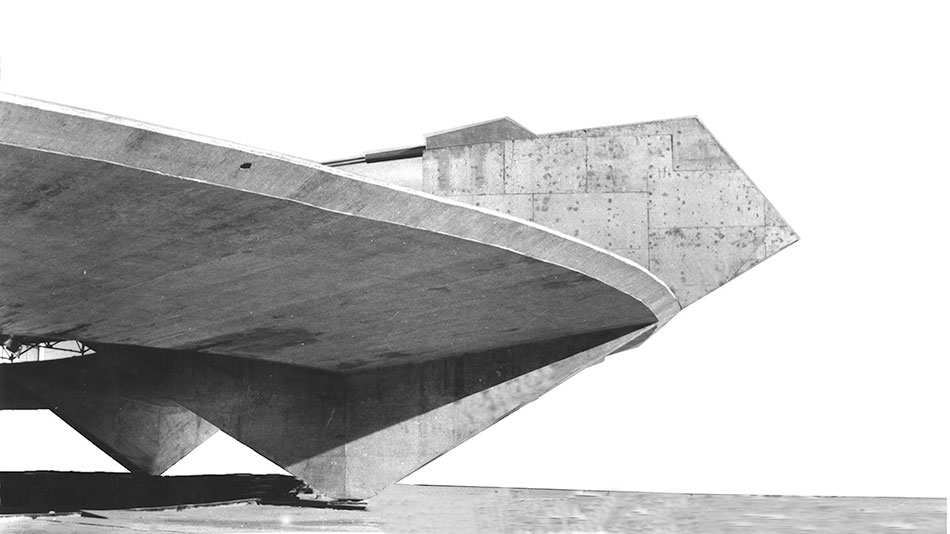

“My work is not about ‘form follows function’, but ‘form follows beauty’ or – even better – ‘form follows the feminine’,” says Oscar Niemeyer. Niemeyer’s Museu de Arte Contemporânea (MAC) in Niterói dances at the foot of a cliff using the sea and sunset as a backdrop. There is something whimsical and confident about the concrete building – it is a bit like Ana, feminine and curvaceous with a strong foothold on the earth on which she stands. Brazilian dancers are confident and not so concerned with their proportions, size or age. They are vain and also seem to accept the unnatural as being a part of life – almost on a par with the natural – many having undergone cosmetic interventions to enhance their anatomy; they celebrate imperfection and individual taste.

The Museu Brasileiro da Escultura (MUBE) in Sao Paulo, designed by Paulo Mendes da Rocha, is confident and stands proud with its rough concrete finish, exposed, celebrating imperfection. The building creates the ground and floats above it, with a structure that contains services and lighting to illuminate the crafted concrete garden beneath, a magical place for sculpture to be exhibited and enjoyed both externally and internally.

It comes as no surprise that expats such as Italian architect Lina Bo Bardi have been drawn to practicing architecture in Brazil, and have flourished. I get the impression that in Brazil she found the comfort and freedom to experiment with her style – with beautiful, honest buildings that dance with the people and community, forming spots of refuge from both the city of Sao Paulo and the rain.

Two examples of her buildings that do exactly the latter are the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) and Serviço Social do Comércio, Social Service of Commerce (SESC). The MASP is located on the busy Avenue Paulista in Sao Paulo which is lined with high-rise buildings where, at one point, a shaded piazza is created, breaking the monotony of the street-scape. The MASP has four red legs that elevate it from the pavement. Here, while one can enjoy exhibits of Picasso, Rubens and Modigliani in the concrete space above, people congregate in the piazza below, dancing and playing music.

The SESC Pompeia is also a marvellous building composed of two naked, rough concrete blocks that seem to interact with each other like a dancing couple. Its construction, with its rough workmanship, suggests that it has been built by the community. The many bridges – that still have the texture of the timber imprinted upon them and are used for the shuttering between the two orthogonal volumes – animate the building, creating a scene of interaction and movement.

“Brazilian dancers are confident and not so concerned with their proportions, size or age. They are vain and also seem to accept the unnatural as being a part of life”

It can easily be described as unfinished, ugly, strange, different, etc., but it certainly stands out confidently above the buildings surrounding it, with its raw concrete attire and red polka-dot windows. It is a celebration of individuality, self-confidence and the man-made, offering a safe haven for leisure and culture to flourish in the busy city of Sao Paulo. “I never disregard the surrealism of the Brazilian people, their inventions, their pleasure in gathering together, dancing, singing… Therefore I dedicated my work at Pompeia to youngsters, to the children and to the third age: all together,” says Lina Bo Bardi

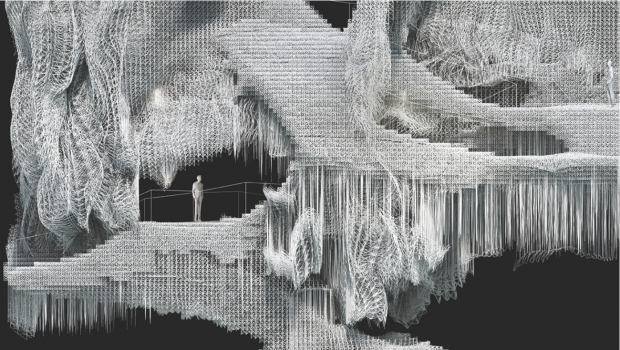

Capoeira, also practised at the SESC Pompeia, is the one and only original Brazilian martial art – invented and practised by slaves in the past and disguised in the form of a dance. A rhythm is played on a berimbau (a single-string percussion instrument, a musical bow) to which the practitioners, facing each other, repeat a series of steps, exchanging acrobatic kicks intentionally missed and dodged and creating a spectacular choreography to the beat of a drum.

As an architect, a lesson learnt from Brazil is that good buildings are just like capoeira. They are a means of shelter that also manage to dance – let’s SAMBA!