Tropical Alchemy

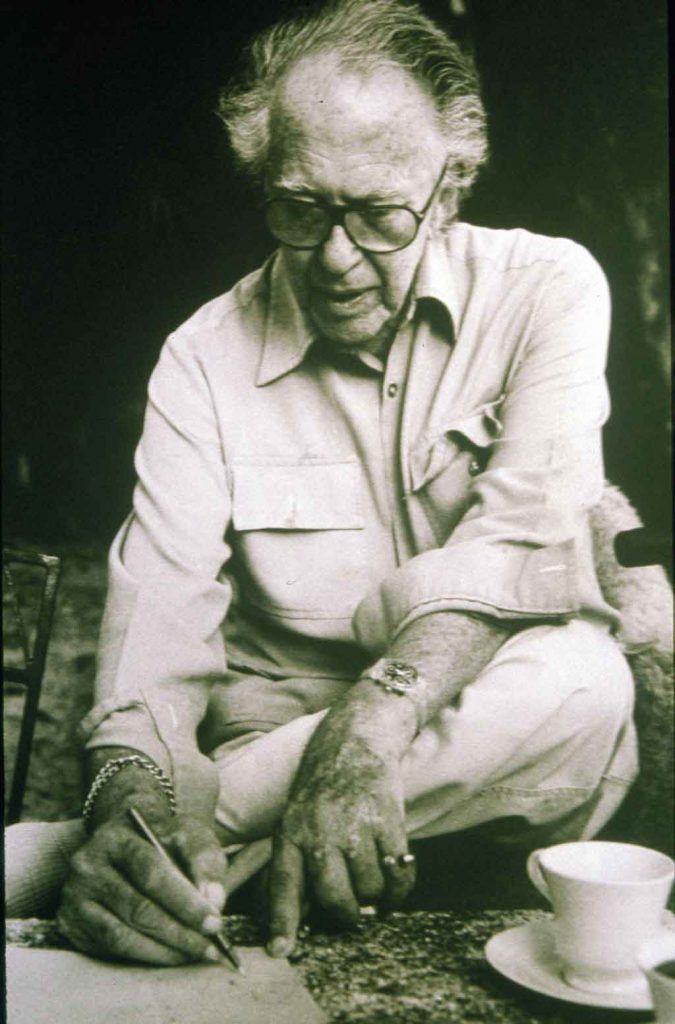

Discovering the founding father of Tropical Modernism, Sri Lankan-born Geoffrey Bawa, whose work radically transformed the architectural landscape across South East Asia and beyond.

Words by: Rossella E. Frigerio

Almost all of my life threads back into Asia.

Years spent growing up and traversing what were then the lesser-known corners of the Orient fuelled my love of buildings with wide, ventilated spaces that embraced the tropical vegetation, embodied local building materials and kept temperatures naturally cool.

It was only when I visited Sri Lanka at the very end of its decades-long civil war that I realised that such design elements were synonymous with a distinct architectural movement – Tropical Modernism – the founding father of which was Sri Lankan-born Geoffrey Bawa.

Bawa has acquired something of a superstar status within his home country, and it is not uncommon to chance upon a private bungalow, hotel or governmental building bearing the Bawa hallmarks in the most remote corners of this dazzling island.

Born in 1919 in Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then known, Bawa read English at Cambridge University and studied law in London. He returned home in 1946 to begin his legal career, yet soon tired of the profession.

After several years of further explorations, he bought a derelict rubber estate at Lunuganga, near Bentota, with the aim of transforming it into a tropical evocation of an Italian garden.

The year was 1948, and it would mark the beginning of his prolific journey as one of Asia’s most influential and innovative architects whose portfolio of designs would span from India to Indonesia to Fiji.

This translates into sloped roofs, overhanging eaves, internal courtyards, ponds and glassless windows – each implemented to enhance openness, ventilation, natural lighting and privacy. Integral to his designs is the use of locally-sourced materials and locally-trained craftspeople, harmoniously blending the building with the local landscape both aesthetically and socially.

For Bawa, the ultimate objective was to produce a spatial experience rather than a visually prominent and symbolic structure. As C. Anjalendran, his former assistant notes. Encompassing both a revival of the past and a drive towards a new future, Bawa became an icon, inspiring a new generation of talents internationally – from Kerry Hill in Australia to Mok Wei Wei in Singapore and Ernesto Bedmar in Argentina.

Ahead of his centennial celebration next year, we shine a spotlight on several of his iconic projects suffused with Sri Lanka’s 2,500-year-old architectural heritage and tropical alchemy.

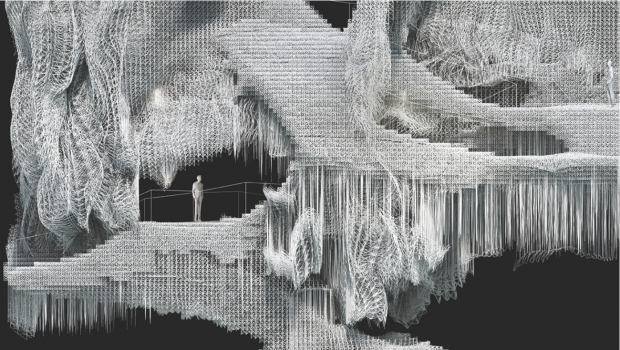

The Kandalama Hotel, Dambulla, (1992)

The Kandalama Hotel was the first of Bawa’s designs to be carried through to completion when he set up his own design studio.

When taken to inspect a proposed site near the foot of Sigiriya Rock, he rejected it and suggested instead that the hotel be built upon land overlooking the ancient Kandalama reservoir some miles away to the south that would give distant views of the Rock.

With some difficulty, the party drove to the north side of the reservoir and looked across the water to the cliffs where Bawa proposed to build. After overflying the site in a helicopter, the proposal was accepted.

The hotel was built on a ridge against the north-facing cliff and enjoys spectacular views across the reservoir. After travelling along jungle tracks, visitors have swept up a steep ramp to the hotel’s cave-like entrance.

A corridor snakes through the rock and leads to an open lounge where one may catch the first glimpse of the reservoir and distant Sigiriya. The building, with its stark and understated architecture, seamlessly disappears into the surrounding lush jungle.

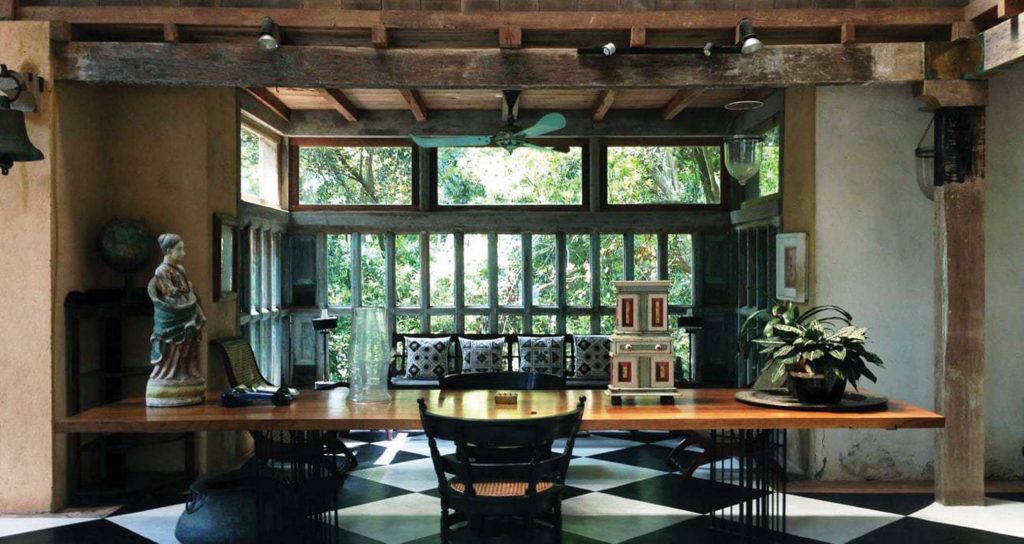

Lunuganga, Bentota (1948 – 1998)

This is Bawa’s own beloved country house in Bentota, on Sri Lanka’s southwestern coast, and the most celebrated home in the architect’s portfolio. Every corner of Lunuganga is designed to maximize the setting’s natural beauty.

Bawa conceived areas that were to be enjoyed at various times of day, depending upon the position of the sun: a southern terrace for breakfast in the mornings, with a view toward a Buddhist shrine on a distant hill; a lunch table under a jackfruit tree, with a bell salvaged from a temple used to summon the staff; a shady spot for afternoon tea; a sunset corner with space for a few folding directors chairs; and a dining table in a veranda near his favourite frangipani tree.

The Gallery Cafe, Colombo (1961)

Now a popular art gallery and café run by Paradise Road, this building was first built in 1961 for a client, and then subsequently acquired by Bawa for his architectural offices. Designed as a series of pavilions separated by courtyards, the style blends both traditional Sinhalese with Dutch colonial traditions.

The design incorporates a number of Bawa’s characteristic innovations including turned timber columns with granite bases and capitals and projecting windows with lattice shutters.

About Rossella E. Frigerio

Formerly one of Dame Vivienne Westwood’s legal advisors and co-founder of luxury accessories brand Sofia Capri, Rossella is currently based in Malta where she is the co-hotelier of her family’s boutique hospitality concept, Locanda La Gelsomina. A strong believer in positive, genuine collaboration, she has co-founded the Malta Creative Collective and launched consultancy brand One Blue Dot, which guides emerging ventures that hold a positive and global vision.