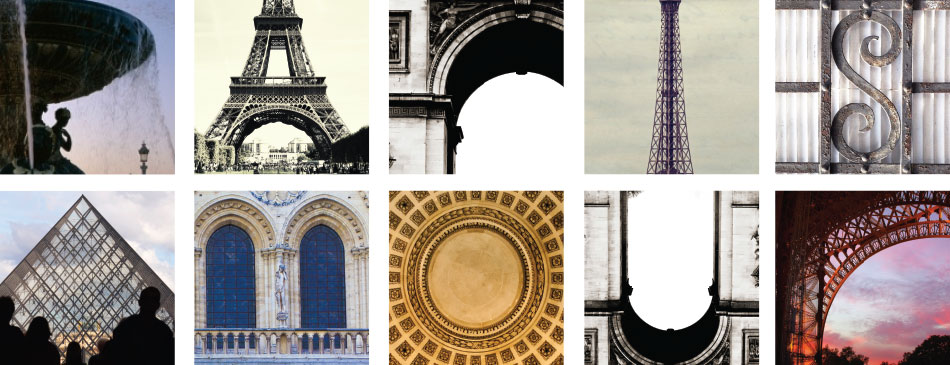

Paris mon amour

The arrival of the euro in Paris in the summer of 2002

France’s far-right party, Le Front National, worryingly made it to the second round of the Presidential election; the winner of that election, Jacques Chirac, escaped assassination by a neo-Nazi during the Bastille Day parade on the Champs-Elysées; and Paris’s Mayor Delanoë (who was stabbed in October for “being gay”) had the imaginative idea of covering parts of the concrete banks of the River Seine with sand so that the citizens of the city could enjoy their very own “beach” in the heart of the city. It was also, according to Meteo France, the second hottest year since 1949 and the city was ablaze with World Cup fever.

I settled into Paris’s African quarter in the 18th arrondissement, just in time to experience the five-day, all night-ers of car-horn honking and shrieking as my neighbourhood celebrated Senegal’s victory over Sweden. Paris was hot, hostile and not at all like the Amelie Poulain film I had seen before arriving. I was even living below the famous Montmartre Hill that featured in Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s sugar-coated biopic. But it didn’t take me long to realise that the top part of that hill was reserved for tourist-trappers, rich Americans and depressed painters. At its base were the impoverished immigrant communities, the prostitutes, addicts and a few tourists walking around asking “Where’s Montmartre?”

I had left behind me in London a place at a top university that I couldn’t afford to go to, a single bed in a shared room in a young worker’s hostel off the Earl’s Court Road – a hot spot at the time for Australian barmen and Kosovan refugees. three simultaneous part-time jobs in a pub, a cocktail bar and a nightclub, managed by three different – yet similarly coke-fuelled bosses, a handful of friends that still lived at home with their parents, an angry ex-boyfriend and a feeling that life wasn’t fair. Paris was meant to be a few months away to reflect. It turned into 12 years.

I never planned to stay. Each year, for 10 years, I would tell myself that this would be the last. But it didn’t happen. I became used to the French language, the French lifestyle and the French raison d’être and I wanted to be accepted as one of them. In fact it was so difficult to not feel like a recipient for the general public’s disdain for all things British – from 2002 onwards I would receive an endless tirade from anyone met me about Mad Cow disease, Britain’s lack of gastronomic culture, the Iraq war, Tony Blair’s misdoings, Britain not accepting the euro, our inability to pronounce the word ratatouille, Mr Bean and the Hundred Years’ War – that it became a challenge for me to become more French than the French. I worked in Paris’s trendy bars and restos, cultivating a permanent blasé look that said “I don’t give a s**t, I’m Parisian, you schmuck”. I studied History at La Sorbonne and joined the student demonstrations in 2006, learning to appreciate the sweet smell of tear gas and burning rubber, all the while imagining I was in some sort of May 1968 remake set against the historical backdrop of the Latin Quarter. I learned to speak French like a native, quickly picking up all those Gallic shrugs and huffing noises that made me look more credible. These days, if a French waiter talks to me in English because he hears me talking with an English colleague or friend, it is I who pompously replies to him in snappy, shruggy French.

The challenge completed, however, I still stayed. I don’t ask myself why anymore.

It seems that there are just over 20,000 Britons living permanently in or on the outskirts of Paris. For a number of reasons it seems: love, family, work, the food, a better lifestyle, the long lunch breaks, the wine, the fact that Paris is so beautiful that you feel as if you are permanently starring in your own film, that Paris is composed of 20 small villages that are totally different from each other, and because everyone I have met who stayed in Paris has said the same thing – Paris is like a vacuum, sucking you in, a lover’s hold, an indescribable force that keeps you coming back.