Unfixed

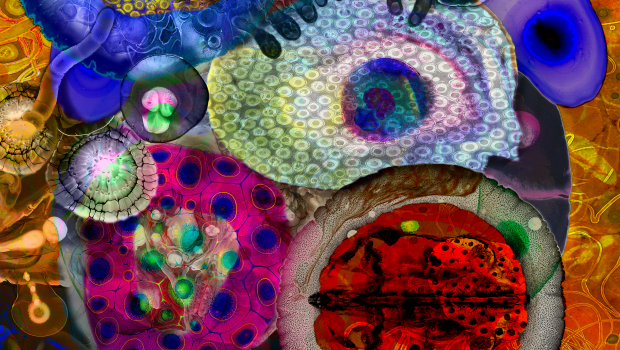

Nothing in Kathrine Maj’s world stays still. Her drawings pulse with movement, bodies bending, merging, vibrating on the edge of becoming.

Interview by Prof. Charlene Vella

Rendered in charcoal, her work is fast, instinctive, and alive with contradiction: beauty and brutality, intimacy and distance, softness and rage. At the centre is the female form, not idealised, but felt. Through limbs, lines, and smudges, she captures something primal and deeply human. This is not about perfection. It’s about presence. A visual language of emotion, memory, and myth, drawn in dust and nerve.

Kathrine, your drawings are raw, powerful, and sometimes unsettling. How do you describe what you do to someone who isn’t into art?

It’s about many dualities: strength, power, vulnerability, creation, sexuality, exhaustion. I’m fascinated by how these opposites exist in one form, not just for women today, but also for our ancestors. When I draw, I feel connected to the concept of what it means to be a woman and a human. It’s about life, passion, connection, and sometimes rage, showing that we’re all part of a larger continuum.

Kathrine, your drawings are raw, powerful, and sometimes unsettling. How do you describe what you do to someone who isn’t into art?

It’s about many dualities: strength, power, vulnerability, creation, sexuality, exhaustion. I’m fascinated by how these opposites exist in one form, not just for women today, but also for our ancestors. When I draw, I feel connected to the concept of what it means to be a woman and a human. It’s about life, passion, connection, and sometimes rage, showing that we’re all part of a larger continuum.

How has living in Malta influenced your work?

Immensely. Especially Malta’s matriarchal past and its ancient temples. Since moving here, I’ve been looking more closely at church sculptures, traditional iconography, and the way women are represented in sacred spaces. It’s interesting to reinterpret those symbols through a contemporary, female lens.

You often include animals, especially dogs. Tell us about that.

The dogs are inspired by the Kelb tal-Fenek, the Maltese hunting hound. I see them as ancient, spiritual creatures. They’re part of Malta’s history but also seem foreign and otherworldly. When I moved to Malta from Denmark, I became obsessed with them. I saw them as stubborn and agile, but also elegant and loving. In my drawings, they appear as companions, guardians, sometimes as extensions of the women themselves. They blur the boundary between human and animal, a duality I find very appealing.

There’s a lot of movement and emotion in your drawings. They almost seem to vibrate. Where does that come from?

I use charcoal because it lets me move fast. It smudges, it reacts to pressure, it’s unpredictable. When I start drawing, I don’t have a finished image in mind; it’s always an organic process driven by impulse. I often leave “mistakes”, or what in art history would be termed pentimenti, visible because they feel honest. They are traces of the element of chance that comes with working in charcoal.

There’s something almost mythological about your compositions. Do you think of them as stories?

In my work, I refer to paintings by masters of various periods, especially the Medieval, Renaissance, Neoclassical, and Pre-Raphaelite eras. These influences from our shared art history and visual culture are reinterpreted and perhaps give the work a quasi-mythological feeling. Something that feels both familiar and alien. Sometimes the result looks like a scene from a forgotten legend, but it’s all very intuitive and abstract.

Your figures often merge together — bodies overlap and morph into one another. What does that represent?

It’s about connection and transformation. I’m fascinated by liminality, the in-between states where one thing becomes another. Life isn’t fixed; everything is always shifting, physically, emotionally, spiritually. The merging of figures in my work is my way of exploring that constant state of becoming.

The female figure is central in your work. What draws you to it?

The female body is fascinating because of its many dualities: strength and vulnerability, power and softness, creation and exhaustion. It holds history, memory, and emotion. Through it, I can explore what it means to exist, to feel, and to transform.

Do you ever find your work too revealing, given how intimate it is?

Sometimes, yes. Drawing the body can feel like exposing your own nerves. But art only works if you’re vulnerable. I think people connect to honesty, so I try not to censor myself. The discomfort and confrontation are part of the process; they’re what give the work energy.

What’s your studio routine like? Do you listen to music, or is it all silence and focus?

It’s a bit chaotic! The artmaking process is very organic and free — there’s no point in trying to keep things neat and clean. I draw for many hours at a time, usually with jazz music, my dog snoozing in a chair next to me, plenty of coffee, and charcoal dust everywhere.

What do you hope people feel when they stand in front of your drawings?

I hope they feel something, even if they can’t name it. Maybe recognition, maybe discomfort, maybe tenderness, maybe confusion. It’s all valid, and it’s all about feeling.