From Runways to Reality

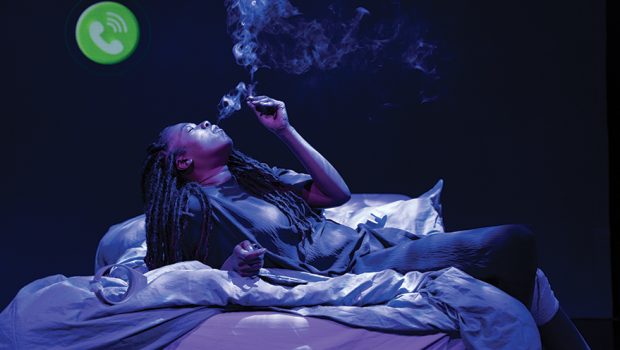

Modeling, Mysticism + Making Meaning with Adi Neumann, Photography by Ron Kedmi

For more than a decade, Adi’s face was everywhere, from global fashion campaigns to icy fragrance sets and wild locations in Iceland and Mexico. Today, she moves between spiritual teaching, Kabbalah, kundalini yoga, psychedelics-informed work, and a new podcast that weaves all of those worlds together. In this conversation, Adi looks back at the most meaningful moments of her modeling career, the experiences that cracked reality open, and how a search for purpose led her from New York runways to inner work, start-ups, and spiritual guidance.

You had a remarkable modeling career. Looking back now, which moments or collaborations feel the most meaningful?

The ones I remember most clearly are the shoots where something happened, where I learned something new about myself or life, not just about clothes or cameras.

One of my absolute favourites was a Puma fragrance campaign called Puma Create. The concept was that another model and I would sculpt a giant ice block into the shape of the perfume bottle, using real chainsaws. They wanted it to look authentic, so instead of heavy safety goggles and huge gloves, we ended up learning how to work with these small, real chainsaws while protecting our faces from shards of ice.

They sent us to this enormous ice warehouse in Brooklyn the day before the shoot. We spent hours in full gear learning how to move with the chainsaw, how to slide in and out of the ice so it felt powerful but controlled. By the end, we were working almost bare-handed, just focused and precise, feeling strangely confident with these intense machines. It was freezing. I ended up with angina and a week on antibiotics afterwards, but it was still magical. There’s something unforgettable about mastering a completely new skill in a very short time.

Another shoot I’ll never forget was in Iceland, over twenty years ago, with the same photographer who shot the Vamp story, Ron. We had long drives between dramatic locations, stopping at natural hot springs and a lagoon full of huge icebergs. At one point they put me in a little boat, took me out to an iceberg in the middle of the water, and shot me alone from far away.

I was standing there, changing looks, posing on this beautiful floating iceberg, and suddenly we heard a loud crack. I felt the ice shift beneath my feet, instinctively lifted one leg, and the chunk I had been standing on just dropped into the water. I sort of slid sideways and ended up on what was now a much smaller iceberg. I stayed dry, but it was one of those moments where you feel how thin the line is between magic and danger.

On that same trip we completely lost track of time because of the endless daylight. I remember telling the crew, “My back really hurts, what time is it?” Nobody knew. When we finally checked, it was 2 a.m. We’d been shooting outside for hours without realising it because the sun refused to go down.

Those jobs weren’t just “good work”, they were experiences that stayed in my body.

You’ve also spoken about supporting younger models on set. Why was that important to you?

There was a photographer, Enrique Badulescu, who used to book me often with very young models, 15 or 16-year-old girls, often on their first lingerie shoots. He would say, “You’re good with them, you help them feel confident.”

We’d be in places like early-2000s Tulum, when there were only a few hotels and real jungle between them. On one job for Etam we were floating on this giant lily-pad raft in the middle of a jungle pond, in lingerie, being pushed around with long poles so it looked like we were fairy nymphs. At some point the rope anchoring our “lily pad” snapped and we just drifted away across the water while the crew screamed from the shore.

Our decorative poles couldn’t reach the bottom, so eventually I half-slid into the water, kept my upper body on the raft, and paddled us back with my legs. When we reached land everyone was relieved, and then immediately told me how dangerous the water was and how I should never put my body in there. I’m glad they told me afterwards.

But beyond the funny stories, what felt meaningful was being able to pass on knowledge I never had as a beginner, how to move energy on set, how not to panic, how to support the crew instead of pushing them to the edge. It was my first taste of mentoring, and I loved it.

What first drew you into modeling, and how did your relationship with the industry change over time?

It started with a very teenage moment. In Israel there was a pageant called Miss Teen Israel, and in 1995 the winner was on the cover of every youth magazine. I remember looking at her photo and thinking, I could do that. That could be me.

Two years later, in 1997, I entered the competition, partly for the experience and partly because the prize was a car. I ended up winning Miss Teen Israel at 15, a week after my birthday. I chose a neon green car on live television, which my brother ended up driving for years because I didn’t even have a licence yet.

Part of the prize was a contract “worth $250,000” with a New York modeling agency. My parents and I later discovered that meant I was effectively tied to that agency until I’d earned that amount through them. Luckily, it was a good agency, Next Model Management, and I stayed with them for seven years. By 16 and a half I’d moved to New York, in the middle of high school, because once you have a New York agency calling with schools and apartments lined up, it becomes hard to say no.

In the beginning I actually felt a bit embarrassed to say, “I’m a model.” I come from a very academic family, both my parents are doctors, and modeling felt shallow compared to that. I used to mumble it, almost looking away. Over time, though, I realised how much the career had given me: independence, travel, exposure to cultures and ideas, and a deep understanding of image and perception.

By my late twenties, after more than twelve years in the business, I was ready for a different chapter. I moved back to Israel to be with my then-partner, and slowly modeling stopped making sense as a full-time life. I wanted purpose in a new way.

You’ve spent many years studying Kabbalah and other spiritual paths. What pushed you onto that journey?

I’ve always been a seeker. Even as a teenager in New York, I remember having a conversation with my brother, who was also my roommate at the time. I was going through a rough patch, a breakup, some career frustrations, and I kept asking, “Why is life so hard? There has to be a reason for these challenges.”

He got worried, thinking I was talking like someone suicidal, and I kept trying to explain, “No, I love life. I know how lucky we are. I just want to understand why the hard parts exist.” That question never left me.

Eventually my brother’s girlfriend, now his wife, suggested we visit the Kabbalah Centre. We walked in together and both connected deeply. That was the beginning of more than fifteen years of Kabbalah study, alongside other teachings.

What Kabbalah and spiritual work gave me was language and structure for things I instinctively felt: that there are no coincidences, that everything is connected, that our inner work matters. It didn’t make life easier or challenge-free; it gave meaning and tools. It taught me how to see hardship as part of a process, not as punishment.

Psychedelics have also been part of your path. How did those experiences change your understanding of self and consciousness?

I was introduced to psychedelics quite young, in my late teens, but I was fortunate. The people around me had years of experience and treated it with respect. Looking back as a mother, I’d probably prefer my own kids to explore those realms later than I did, but I’m grateful for how it happened.

Those early journeys weren’t just giggles and “the walls are breathing.” The friends guiding me would ask questions like, “Can you influence that blade of grass just by looking at it?” or “Do you feel how all of us are connected right now?” Psychedelics showed me, viscerally and beyond theory, that everything is one system, that consciousness is shared.

I often describe it like this, especially in group work: it’s as if several separate computers, our individual minds, temporarily plug into a bigger supercomputer, a shared field. We each remain ourselves, with our memories and histories, but there’s a larger neural network connecting us. You can feel it in the way ideas ripple through the room, or how everyone senses when one person isn’t telling the truth.

One of the most powerful aspects is that in altered states, you can’t lie to yourself. If you say something that isn’t fully true, you feel the dissonance immediately. Over time that becomes a mirror. You see where you’ve been hiding pain, protecting old stories, or clinging to identities that don’t fit anymore. It can be confronting, but also incredibly liberating.

For me, psychedelics were like being shown an invisible chair. Once you’ve sat on it and felt it hold you, you don’t need anyone to convince you that it exists. That direct experience made it much easier for me to trust spiritual work later. I already knew there was more than the visible world.

After fashion, you moved into startups and education. Where did that shift come from?

I realised I needed my work to matter in a deeper way. After modelling, my first big project was an urban agriculture startup. I loved the idea of growing food where people live, for sustainability, nutrition, and simply having more green life in cities. It was meaningful in theory, but I eventually understood that it wasn’t my personal passion.

My next venture, which I co-led for over six years, did ignite something much deeper: an educational startup for ultra-Orthodox men in Israel. Many of them had spent their lives studying only religious texts, with little exposure to maths, English, or science, which meant they were locked out of the tech sector, the country’s fastest-growing industry.

We built an intensive programme that combined foundational maths, English, and science with a full coding bootcamp, all packed into about a year and a half. Most of the men were in their late twenties or early thirties, often with several children, so time and financial pressure were intense. We used an income-share model and helped them secure loans to support their families during the course.

Watching them graduate, enter the tech world, and change the trajectory of their families’ lives was profoundly moving. It was the first time in my professional life that I woke up sick and still wanted to go to work because people were counting on me. It gave me a taste of soul-level purpose, not just brain or body engagement, but something that made my whole being say, yes, this is why I’m here.

You’re now launching a podcast around Judaism, Kabbalah, and spirituality. What inspired it, and who is it for?

For years, friends, communities, and synagogues have invited me to speak, especially secular or culturally Jewish people who are spiritual but feel disconnected from traditional religious spaces. They’re seekers, but they don’t necessarily see themselves reflected in the old frameworks.

At the same time, we live in an incredible era of access. With a phone and an internet connection, you can take a yoga nidra class, listen to a Tibetan Buddhist teaching, or hear a physics lecture about consciousness. I started to feel that I might have something specific to contribute, a bridge language between Jewish mystical teachings, everyday life, and the wider spiritual landscape.

The podcast grew out of that. It’s for anyone who feels curious, Jewish or not, religious or not, and wants another set of tools to understand themselves and reality. Kabbalah is, in many ways, a sophisticated technology for the mind. Yoga works through the body, psychedelics through expanded perception, Kabbalah works through ideas, symbols, and patterns. All three, for me, are pathways to the same place: oneness.

I don’t want to convert anyone to anything. I want to offer distilled wisdom that’s been refined over thousands of years, in a language that feels modern and accessible, and invite people to weave it into their own journeys.

After so many years in fashion and media, what does beauty mean to you now?

Beauty, for me, is much less about perfection and much more about authenticity and care.

There was a time when I felt conflicted about my looks and my modelling career. Coming from an intellectual family, I worried that being “the model” made people assume I was shallow or unserious. Over the years, that softened. I’m grateful for my body, for my face, and for what that work allowed me to see and learn.

But the older I get, the more beauty I see in how someone lives in their body, in softness, in presence, in how they hold space for others. I see beauty in women who are fully themselves, in lines that tell a story, in a face that has cried, laughed, and kept going.

I also see beauty in simplicity: in a clear table in the morning, in a room with enough space for breath, in a small ritual of brushing out the day before sleep. It’s not about owning the fanciest objects; it’s about tending to the spaces we inhabit, including our own skin, with respect.

All women are beautiful. That’s not a slogan; it’s almost biological. We are built to hold life, to hold space, to change with the cycles of the moon. When a woman connects to that and lets herself be seen as she is, that’s the kind of beauty that moves me now.

And finally, if you had to describe the thread running through all these chapters, fashion, psychedelics, Kabbalah, startups, motherhood, what would it be?

Curiosity, and a refusal to believe that what we see on the surface is the whole story.

Whether it was learning to use a chainsaw on a block of ice, standing alone on an iceberg, guiding younger models, sitting in a Kabbalah class, or helping someone change careers at thirty with four kids, I’ve always been drawn to moments where a deeper layer reveals itself.

I think my work now, with the podcast and everything around it, is about sharing those layers. Saying: there is more, and you already have access to it.