Between Chaos & Calm

Inside the Studio of a Bali-Based Artist Jean-Philippe.

In a quiet studio in Bali, surrounded by the hum of nature and the rhythm of creation, a European-born artist has spent decades shaping a practice that merges philosophy, spirituality, and form. His work bridges two worlds, Western technique and Balinese sensibility, to explore themes of duality, transformation, and the beauty of imperfection. Through his painting and photography, he seeks not mastery, but meaning.

Could you describe a typical day in your Bali studio?

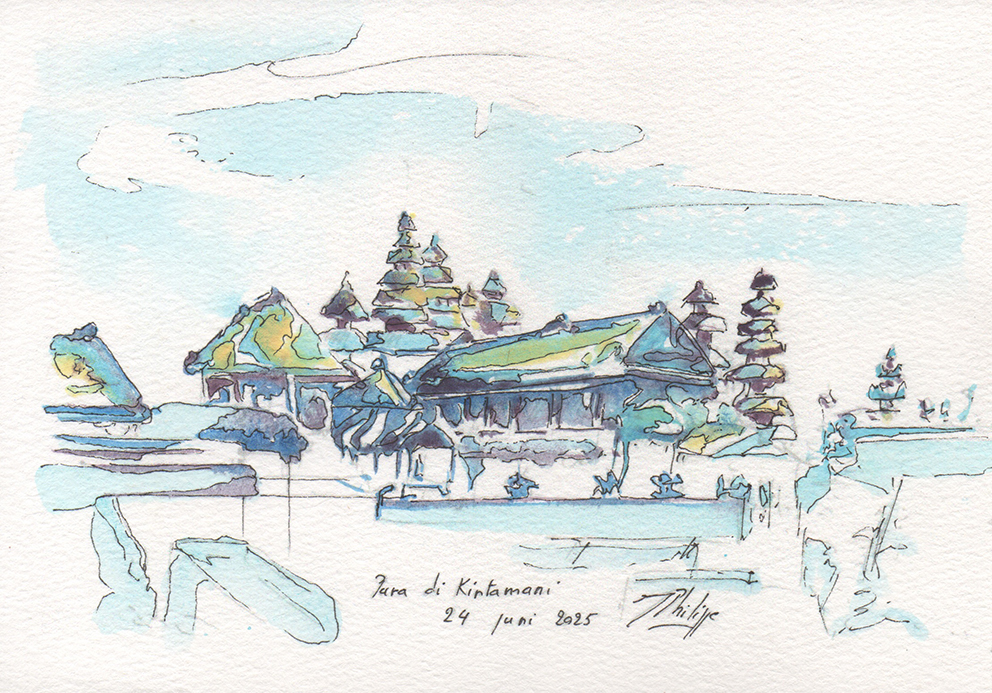

As often as possible, I dedicate the early hours of the day to drawing on a coloured background or preparing a new one, usually until around eleven in the morning. When the heat of the day arrives, I move to my woodworking studio to prepare frames or create furniture. Evenings are devoted to reading sociology, philosophy, or history. Once a week, I take my motorbike to explore the island, sketching a landscape or temple, and taking photographs for future paintings. Whenever possible, I join life model sessions with fellow artists to draw directly from the human form.

How has living in Bali influenced your identity as an artist?

I have lived in Bali since I was twenty-one. I first arrived as a volunteer to run a small art school in Gianyar and never left. My identity now lies at the crossroads of two cultures, my French education and my Balinese life. What began as influence has become reality. I no longer see myself as a visitor but as part of this environment.

How would you describe your approach to painting?

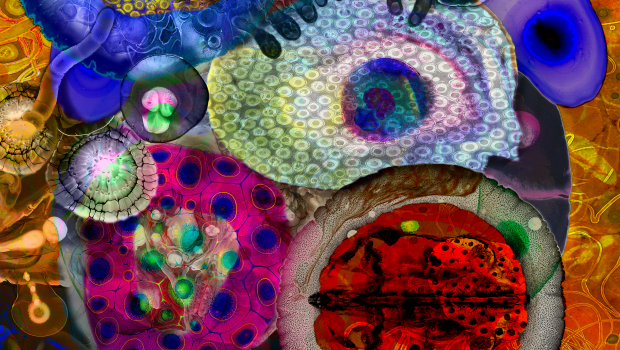

I work in two stages. First, I prepare a coloured background by flooding the surface and applying diluted pigments and water-based media. The natural flows and movements create unexpected textures. Once the surface dries, I use coloured pencils to build my composition, often inspired by my photographs.

What underlies this process is the creation of chromatic chaos. It requires letting go of control and allowing the unexpected to appear. The second stage, the realistic drawing, emerges from this interplay between intention and chance. It becomes a conversation between order and intuition, between the seen and the felt.

Do your photography and painting influence each other?

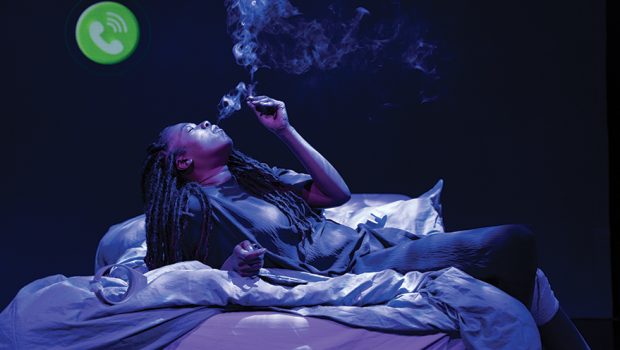

Absolutely. I take photographs with painting in mind. They are not photographs for their own sake, but rather visual archives that feed my paintings. My subjects are the people around me, neighbours, shopkeepers, farmers, dancers, those who fill my daily life.

How does the atmosphere of Bali shape your creative work?

During my art studies in Europe, I often felt confined by a nihilistic and overly conceptual environment. Coming to Bali was like breathing fresh air. Here, creativity belongs to a shared culture of artisans and artists, not to individual ego or ownership. This has given me freedom, not only in my work, but in how I understand art itself. Art, to me, is born from craft, community, and shared creation.

Your work often references duality, passages, and spiritual transformation. How do these appear in your practice?

Duality reflects my two cultures and the ability to see myself from both perspectives. Passages are synchronicities, the fleeting moments and encounters that guide creation. My work often begins with chaos, not to express my ego, but to move beyond it, toward something larger and unexpected. These moments of passage reveal worlds that are psychological, spiritual, and deeply human.

Is there a project that marked a turning point in your journey?

Yes, a painting called The Old Man. I presented it in hopes of joining the Bamboo Gallery in Ubud, which was a major venue for collectors at the time. The gallery accepted the piece but refused to sell it. The director told me, “You must first understand how you made it before we can sell it.” He was right. That painting had a quality that emerged unconsciously, almost by accident. It led me to study chaos theory, the setting aside of ego, and the beauty of synchronicity.

Have you faced creative challenges, and how do you overcome them?

Even in this so-called paradise, I am still a child of my generation, and mornings can be difficult. Doubt and melancholy remain familiar. I turn to Saint Benedict’s rule, which divides the day into three parts: prayer, work, and study. Prayer restores my focus, work channels my energy, and study expands my understanding. Whether the work succeeds or not matters less than showing up for it.

Which philosophical or spiritual influences guide your work?

I hesitate at the word “decision.” Art does not come from decision, but from practice. You can decide to practise, but art itself arises through doing and knowing. My influences are the great Christian mystics, Saint Benedict, John of the Cross, and the Gospel, which I read daily. I am also inspired by thinkers like Bergson, Nietzsche, Bourdieu, and Jankélévitch, who explore the limits of expression and the nature of creation.

Have you faced creative challenges, and how do you overcome them?

Even in this so-called paradise, I am still a child of my generation, and mornings can be difficult. Doubt and melancholy remain familiar. I turn to Saint Benedict’s rule, which divides the day into three parts: prayer, work, and study. Prayer restores my focus, work channels my energy, and study expands my understanding. Whether the work succeeds or not matters less than showing up for it.

Is there a question you wish interviewers asked more often?

Perhaps not a question, but a reminder: the value of the useless. To step away from numbers, statistics, and measurable outcomes, and simply play with colours and shapes. Nothing could be more useless, and yet nothing more essential.