Fashionable fortress

Goldfinger – he was James bond’s nemesis, wasn’t he?

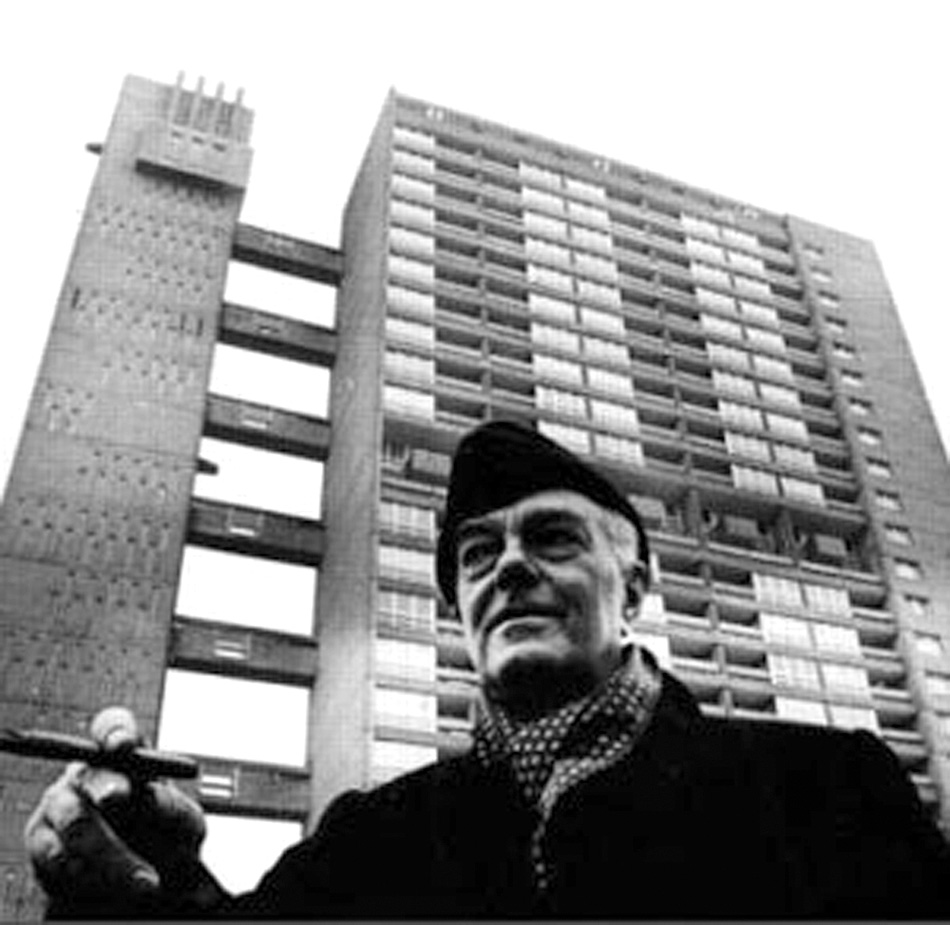

Erno Goldfinger designed some of London’s most brutal buildings in what is now seen as an iconic period in English modernism. In fact, for a time he was alongside Berthold Lubetkin and Denys Lasdun – the pin-up designer for the capital’s trendiest and most outspoken architects and critics. Goldfinger, an émigré from Hungary, arrived in London from Paris in 1934, leaving friends such as Adolf Loos and former mentor Auguste Perret. On arrival in London, the young, tall and famously intimidating immigrant married an heiress of the Crosse & Blackwell table sauce family – which did not deter him from holding close ties with Communists.

In fact, Goldfinger’s life is full of contradictions. While some friends – especially women – found him charming, others were lashed by his sharp tongue: “You’re fired” was a phrase often heard in the Goldfinger office. However, in spite of his left-wing views, he was a favoured designer for speculative office blocks because of his ability to squeeze rentable space out of a small footprint.

But once Peter and Alison Smithson and other leading polemicists for Brutalist architecture had taken him up, Goldfinger turned to public building with unforgettable results. His first chance to build a high-rise public building came in the form of Balfron Tower, which was completed in 1967 in the then deprived East London borough of Tower Hamlets on an imposing location just above the northern exit from the Blackwall Tunnel. This 40-storey tower, the centrepiece of a large new housing development that was intended to form part of a series of such developments around London, rose like a gigantic concrete grid, linked by bridges at three-storey intervals to a freestanding lift-tower. This dramatic composition created a silhouette that is instantly recognisable on the London skyline.

The Balfron Tower marks the eastern edge of the centre of the city. Goldfinger’s masterpiece, the Trellick Tower of 1972 – located just off Ladbroke Grove in North Kensington – marks the western boundary. Goldfinger’s biographer, Nigel Warburton, has aptly described them as two “bookends”, with the city wedged between them. The Trellick has much to tell us about progressive artistic currents in the early 20th century and how Goldfinger worked with them to create a striking and careful composition, a far cry from the standard concrete high-rise blocks that gave the genre such a bad reputation.

It’s possible to read into the carefully gridded façades an interpretation of Mondrian’s delicate proportions between voids and solids; of vertical to horizontal hierarchies; and of changing subtle and balanced relationships between major and minor delineating elements. Admirers of Perret’s own concrete experimentation of the 1920s will also recognise how much Goldfinger drew on this to create this remarkable and unprecedented structure. A stained glass window in the lobby of Trellick Tower, designed by Goldfinger, uses Mondrian themes to mark the division between the public lobbies and the private areas in the building. A careful study of this building as it looms high above the railway and the Victorian terraced houses in the area will therefore reveal to the trained eye a great deal about some of the most adventurous programmes in 20th-century architecture. In the words of one architect living nearby, “the day will come when millionaires will be fighting over the flats in the block” with views well beyond the edges of London – and, furthermore, because of the stringent space standard in the public housing of the day, the rooms are spacious and bright. And yet – there is scarcely a building more controversial amongst those who are uncomfortable with modern architecture. A recent writer in the Guardian, the national broadsheet newspaper read by creative types, used the Balfron Tower as an example of the type of thing admired by hypocritical architects who themselves choose to live in “a Georgian house in Royal Greenwich”. Goldfinger’s own experimental and short-lived residency in Balfron Tower was presented as a patronising gesture that came as a mystery to the people who had the misfortune to live in any of the 40-odd storeys beneath his penthouse.

That architect who foresaw the day when the flats would become prestigious residences may yet have the last laugh. Twenty years ago, bad maintenance and inadequate security had brought both projects to the stage where they had become notorious for crime and insalubrity. A thorough programme of refurbishment has resulted in Trellick Tower once again becoming a safe, attractive, and even exciting place in which to live, to the extent that it has become an icon for the residents of nearby Notting Hill who successfully petitioned for it to become listed as a historic building worthy of preservation. In fact, the tower has ironically become a model of a mixed social development, with long-term council tenants now sharing corridors with the wealthy who have been attracted by the building’s aesthetic credentials.

What this story tells us is that the England worth conserving is not just the country of Ian Fleming’s picturesque villages and Pall Mall palaces, but also of a dynamic international creative centre that, 50 years ago, produced a series of buildings that have become landmarks in the history of housing, city growth and urban form. Somehow the notion of nostalgia has become associated with a romantic past, and yet the young Brutalists of the 1960s saw themselves as romantics, leading the fight against the British tendency to fall back into conservatism and historicism.

Goldfinger’s own house in Hampstead, North London, created violent opposition from outraged neighbours when he first proposed to build it, yet ironically the building is now owned and cared for by the National Trust – a mass-membership organisation with a reputation for restoring country houses and landscaped gardens. Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower can perhaps be likened best of all to nothing other than a modern version of the ancient fortress, eventually inspiring affection as well as awe.